Watched July 16 - 22, 2007: -- Kinugasa, Imai, Ozu, To and Kabuki

Jujiro / Crossroads (Teinosuke Kinugasa, 1928)

According to JMDB, this was the fifty-fifth film Kinugasa directed (a number he would more than double by the time of his retirement in 1966). This is a somewhat less avant-garde silent film than Kinugasa's Kurutta ippeji (misnamed Page of Madness in English) from a couple of years earlier, but is still reasonably exotic looking. Mostly dark and brooding, with wildly exaggerated acting -- but presented in something approaching a linear fashion, with conventional intertitles. The basic scenario is simple a poor but honest young woman has a younger brother who has gotten himself into trouble due to his hopeless passion for a geisha -- and has also been blinded.

According to JMDB, this was the fifty-fifth film Kinugasa directed (a number he would more than double by the time of his retirement in 1966). This is a somewhat less avant-garde silent film than Kinugasa's Kurutta ippeji (misnamed Page of Madness in English) from a couple of years earlier, but is still reasonably exotic looking. Mostly dark and brooding, with wildly exaggerated acting -- but presented in something approaching a linear fashion, with conventional intertitles. The basic scenario is simple a poor but honest young woman has a younger brother who has gotten himself into trouble due to his hopeless passion for a geisha -- and has also been blinded.  Unscrupulous men try to take advantage of our heroine, using her brother's situation as leverage. He recovers his sight, and goes looking for the geisha and runs into more trouble, creating more unhappiness for his sister. The plot is wildly melodramatic and improbable -- and the cinematography is mostly dark and murky. The copy I saw of this was of poor quality, but I doubt even a better looking version would have won me over. Kinugasa, as director here, strikes me as erratic and haphazard -- as he does in his later films.

Unscrupulous men try to take advantage of our heroine, using her brother's situation as leverage. He recovers his sight, and goes looking for the geisha and runs into more trouble, creating more unhappiness for his sister. The plot is wildly melodramatic and improbable -- and the cinematography is mostly dark and murky. The copy I saw of this was of poor quality, but I doubt even a better looking version would have won me over. Kinugasa, as director here, strikes me as erratic and haphazard -- as he does in his later films.

Dokkoi ikiteru / And Yet We Live (Tadashi Imai, 1951)

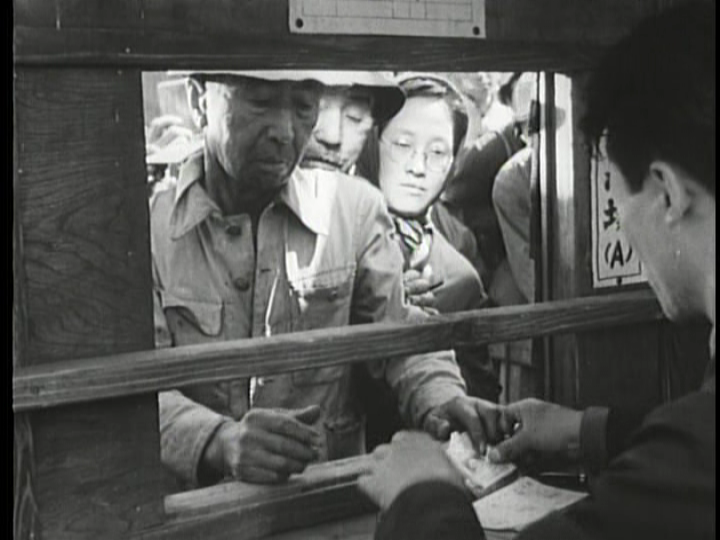

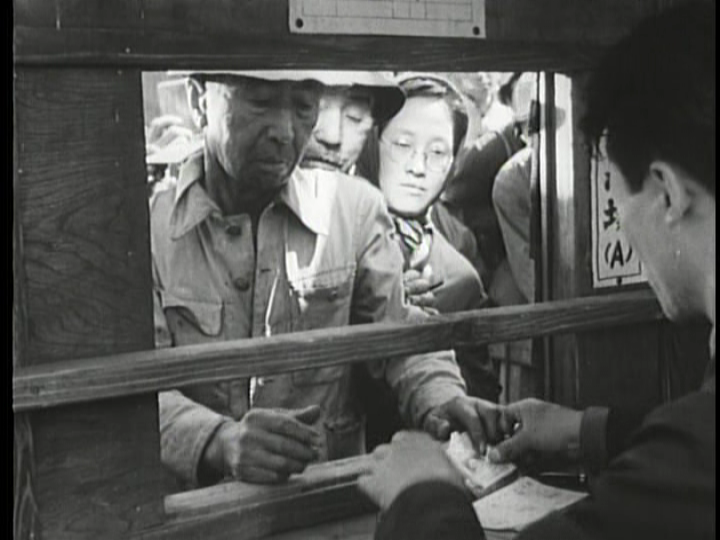

Another excellent Imai film about the plight of the under-privileged. This one deals with displaced workers in Tokyo, trying to earn enough to at least allow themselves and their families to scrape by. The primary focus is on a middle-aged father (Chojuro Kawarasaki) and mother (Hatae Kishi) with two young children. After they lose their shack of a home, Kawarasaki sends his family back to their home village and goes to live in a cheap worker's dormitory.

Another excellent Imai film about the plight of the under-privileged. This one deals with displaced workers in Tokyo, trying to earn enough to at least allow themselves and their families to scrape by. The primary focus is on a middle-aged father (Chojuro Kawarasaki) and mother (Hatae Kishi) with two young children. After they lose their shack of a home, Kawarasaki sends his family back to their home village and goes to live in a cheap worker's dormitory.  Elated when he finds a skilled factory job, he celebrates a bit too much with a shady old buddy (Kanemon Nakamura) and loses the money his old neighborhood friends have loaned him -- for his start at his new job. The job falls through and Kawarasaki goes back to seeking day labor work. Eventually, Nakamura convinces him to help with some illegal scavenger wotk (in a still bombed-out area of Tokyo), based on assurances that such activity was more profitable and entailed little risk. Of course, the two run into trouble.

Elated when he finds a skilled factory job, he celebrates a bit too much with a shady old buddy (Kanemon Nakamura) and loses the money his old neighborhood friends have loaned him -- for his start at his new job. The job falls through and Kawarasaki goes back to seeking day labor work. Eventually, Nakamura convinces him to help with some illegal scavenger wotk (in a still bombed-out area of Tokyo), based on assurances that such activity was more profitable and entailed little risk. Of course, the two run into trouble.  An ellipse finds Kawarasaki re-united with his family -- at the police station. With nowhere to live, the parents are at a loss. Kawarasaki's proposed solution is drastic, spend all they have on a nice day with the children (going to the zoo and having a picnic) followed by suicide for all. His wife continues to oppose the plan (quietly) but agrees to the outing. Late in the afternoon, fate intervenes -- as the couple's son almost drowns while playing with a dilapidated row boat (while the parents are preoccupied with their discussion). The last we see of the father, is his return to the day labor fray, albeit seemingly with a new sense of determination.

An ellipse finds Kawarasaki re-united with his family -- at the police station. With nowhere to live, the parents are at a loss. Kawarasaki's proposed solution is drastic, spend all they have on a nice day with the children (going to the zoo and having a picnic) followed by suicide for all. His wife continues to oppose the plan (quietly) but agrees to the outing. Late in the afternoon, fate intervenes -- as the couple's son almost drowns while playing with a dilapidated row boat (while the parents are preoccupied with their discussion). The last we see of the father, is his return to the day labor fray, albeit seemingly with a new sense of determination.

Imai and his cinematographer Yoshio Miyajima (later a regular collaborator with Kobayashi) did a remarkable job of interweaving documentary-style footage with impeccably composed (yet none-the-less highly real looking) staged scenes. Comments on Imai's works of this sort invariably invoke the influence of post-war Italian neo-realism --

Imai and his cinematographer Yoshio Miyajima (later a regular collaborator with Kobayashi) did a remarkable job of interweaving documentary-style footage with impeccably composed (yet none-the-less highly real looking) staged scenes. Comments on Imai's works of this sort invariably invoke the influence of post-war Italian neo-realism --  and ignore Japan's own pre-war realist tradition (Shimizu, Uchida, Ozu, Yamanaka, Naruse et al.). The link with Yamanaka is especially striking -- as Kawarasaki and Nakamura (both former members of the same left-wing theatrical group) were the two lead actors in his Humanity and Paper Balloons. The rest of the cast, including youngster Isao Kimura and old-timer (and Ozu veteran) Choko Iida also do an excellent job of looking and acting like they were part of the extremely impoverished world the film portrays.

and ignore Japan's own pre-war realist tradition (Shimizu, Uchida, Ozu, Yamanaka, Naruse et al.). The link with Yamanaka is especially striking -- as Kawarasaki and Nakamura (both former members of the same left-wing theatrical group) were the two lead actors in his Humanity and Paper Balloons. The rest of the cast, including youngster Isao Kimura and old-timer (and Ozu veteran) Choko Iida also do an excellent job of looking and acting like they were part of the extremely impoverished world the film portrays.

Like Uchida before him and Yamada after him, Imai was able to portray the plight of his less fortunate countryman with great sensitivity and without condescension -- while routinely exhibiting excellent visual sensibility. For reasons not entirely clear, most Western (or at least American) commentators have been fairly dismissive of the work of Imai. Apparently leftist sensibilities in makers of popular films (as opposed to avant-garde ones) was something that just was (and still is) not tolerable.

Like Uchida before him and Yamada after him, Imai was able to portray the plight of his less fortunate countryman with great sensitivity and without condescension -- while routinely exhibiting excellent visual sensibility. For reasons not entirely clear, most Western (or at least American) commentators have been fairly dismissive of the work of Imai. Apparently leftist sensibilities in makers of popular films (as opposed to avant-garde ones) was something that just was (and still is) not tolerable.

More screenshots:

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/imai/dokko/yet03.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/imai/dokko/yet04.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/imai/dokko/yet06.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/imai/dokko/yet07.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/imai/dokko/yet09.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/imai/dokko/yet11.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/imai/dokko/yet12.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/imai/dokko/yet13.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/imai/dokko/yet14.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/imai/dokko/yet15.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/imai/dokko/yet16.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/imai/dokko/yet17.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/imai/dokko/yet18.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/imai/dokko/yet19.png

Soshun / Early Spring (Yasujiro Ozu, 1956)

In this mid-50s film, Ozu re-visits (for the last time) the world of the salaryman -- a topic near and dear to his heart in the 1930s. Although the economic climate of 50s Japan was decidedly better than that of twenty or so years earlier (when Japan was just edging out of a major depression), the picture Ozu paints of it is, in many ways, bleaker. Ozu is particularly interested here in the impact of the still-developing post-war "corporate culture" on Japanese family life.

In this mid-50s film, Ozu re-visits (for the last time) the world of the salaryman -- a topic near and dear to his heart in the 1930s. Although the economic climate of 50s Japan was decidedly better than that of twenty or so years earlier (when Japan was just edging out of a major depression), the picture Ozu paints of it is, in many ways, bleaker. Ozu is particularly interested here in the impact of the still-developing post-war "corporate culture" on Japanese family life.  Ryo Ikebe and Chikage Awashima have been married for about ten years -- and have gradually drifted apart since the death of their only child. Ikebe's focus has shifted more and more to work and to recreation after work with his colleagues from work, leaving Awashima with an increasing sense of futility. While her mother (Kumeko Urabe) counsels patience, Awashima finds her tolerance levels dropping. The situation worsens when Ikebe is drawn into a romance with a co-worker nicknamed Goldfish

Ryo Ikebe and Chikage Awashima have been married for about ten years -- and have gradually drifted apart since the death of their only child. Ikebe's focus has shifted more and more to work and to recreation after work with his colleagues from work, leaving Awashima with an increasing sense of futility. While her mother (Kumeko Urabe) counsels patience, Awashima finds her tolerance levels dropping. The situation worsens when Ikebe is drawn into a romance with a co-worker nicknamed Goldfish (Keiko Kishi). At around the time Ikebe is asked to "consider" a transfer to a provincial industrial city, Awashima decides she has had enough -- and moves in with her old school chum (Chieko Nakakita). Ikebe, unable to talk to his wife, moves to his new post alone. Along the way the way, he makes a visit to his mentor (Chishu Ryu) who was previously shunted off to a provincial assignment and (inexplicably, to his colleagues) has made no real push to return to the corporate rat race at the home office.

(Keiko Kishi). At around the time Ikebe is asked to "consider" a transfer to a provincial industrial city, Awashima decides she has had enough -- and moves in with her old school chum (Chieko Nakakita). Ikebe, unable to talk to his wife, moves to his new post alone. Along the way the way, he makes a visit to his mentor (Chishu Ryu) who was previously shunted off to a provincial assignment and (inexplicably, to his colleagues) has made no real push to return to the corporate rat race at the home office.  As it turns out, Ryu is pleased to have had the opportunity to spend more time with his wife and children -- and to repair the family relationships frayed by his over-busy professional life in Tokyo. Ryu urges Ikebe to similarly put his temporary posting to productive personal use -- and promises to try to help patch up things between Ikebe and Awashima. One day, on coming home to his rented apartment, Ikebe finds his wife has re-joined him -- and the two, both uncertain and hopeful, begin to think about their future.

As it turns out, Ryu is pleased to have had the opportunity to spend more time with his wife and children -- and to repair the family relationships frayed by his over-busy professional life in Tokyo. Ryu urges Ikebe to similarly put his temporary posting to productive personal use -- and promises to try to help patch up things between Ikebe and Awashima. One day, on coming home to his rented apartment, Ikebe finds his wife has re-joined him -- and the two, both uncertain and hopeful, begin to think about their future.

Ozu's style here (with cinematography by Yuharu Atsuta) has become quite spare -- but their are still traces of camera movement here and there (some of these, traversing empty corridors briefly, are a bit mysterious). The over-riding tone is bleak -- and portions of the film are a bit seedy. A group hike (during which Ikebe and Kishi escape) offers a bit more liveliness, as do the comic interludes presided over by Urabe. But the over-riding tone is considerably more dour than Ozu's norm. It goes without saying that the performances (and script) are first rate. No, perhaps, one of Ozu's most easy to love films -- but one of considerable interest (despite its over two and a half hour length).

Ozu's style here (with cinematography by Yuharu Atsuta) has become quite spare -- but their are still traces of camera movement here and there (some of these, traversing empty corridors briefly, are a bit mysterious). The over-riding tone is bleak -- and portions of the film are a bit seedy. A group hike (during which Ikebe and Kishi escape) offers a bit more liveliness, as do the comic interludes presided over by Urabe. But the over-riding tone is considerably more dour than Ozu's norm. It goes without saying that the performances (and script) are first rate. No, perhaps, one of Ozu's most easy to love films -- but one of considerable interest (despite its over two and a half hour length).

More pictures:

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/ozu/soshun03.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/ozu/soshun04.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/ozu/soshun05.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/ozu/soshun07.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/ozu/soshun08.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/ozu/soshun11.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/ozu/soshun12.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/ozu/soshun14.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/ozu/soshun15.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/ozu/soshun16.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/ozu/soshun17.png

Ngo joh aan gin diy gwai / My Left Eye Sees Ghosts (Johnnie To and WAI Ka-fai, 2002)

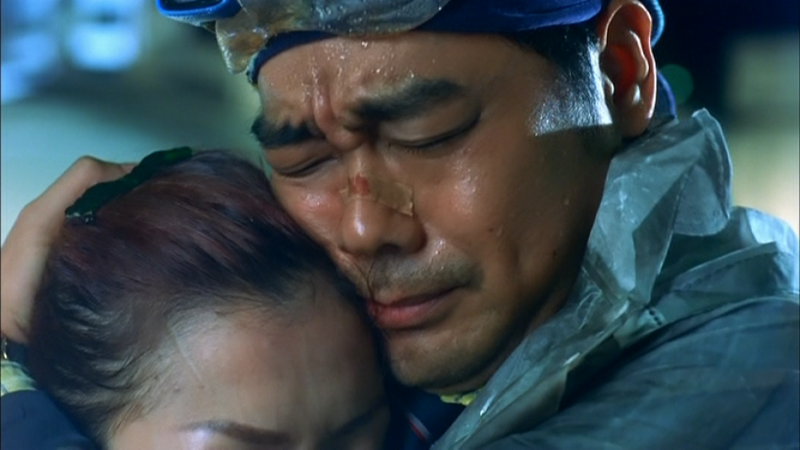

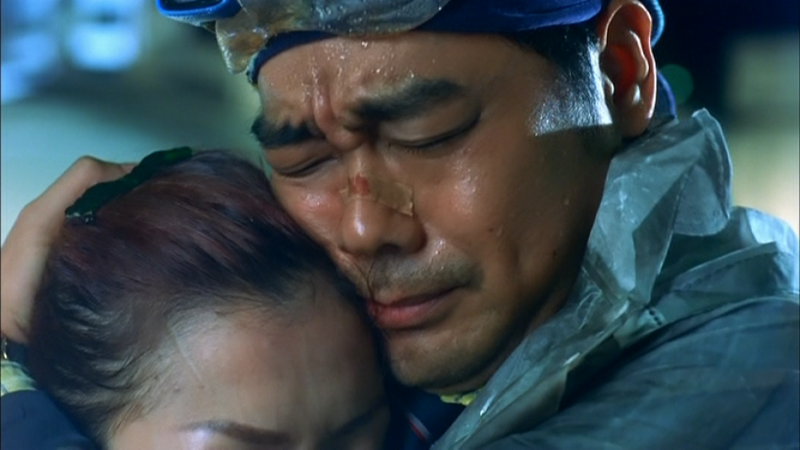

May (Sammi Cheng) falls in love with a rich young man (named Daniel) while on vacation and marries him -- but he dies soon afterward -- leaving his family and friends thinking she must simply be a lucky gold-digger. In fact, she is not able to shake off her grief -- and tries to commit suicide, but is saved by a ghost --

May (Sammi Cheng) falls in love with a rich young man (named Daniel) while on vacation and marries him -- but he dies soon afterward -- leaving his family and friends thinking she must simply be a lucky gold-digger. In fact, she is not able to shake off her grief -- and tries to commit suicide, but is saved by a ghost --  and afterwards she is able to see ghosts, but only with her left eye. With the aid of her father (LAM Suet), May determines that her rescuer ghost must be that of a childhood friend named Ken (LAU Ching-wan). Ken (having died young) tends to behave in a juvenile fashion --

and afterwards she is able to see ghosts, but only with her left eye. With the aid of her father (LAM Suet), May determines that her rescuer ghost must be that of a childhood friend named Ken (LAU Ching-wan). Ken (having died young) tends to behave in a juvenile fashion --  but clearly seems to have had a crush on May (and presumably still does). May has a number of problems -- with both ghosts and with the other females involved in the family business she inherited a part of (Daniel's mother and sister -- and Daniel's long-time, dumped friend). One thinks that the film will mostly be unalloyed silliness, then (as not uncommon), To and Wai shift gears -- and we move into deeper, more moving territory.

but clearly seems to have had a crush on May (and presumably still does). May has a number of problems -- with both ghosts and with the other females involved in the family business she inherited a part of (Daniel's mother and sister -- and Daniel's long-time, dumped friend). One thinks that the film will mostly be unalloyed silliness, then (as not uncommon), To and Wai shift gears -- and we move into deeper, more moving territory.

Sammi Cheng and LAU Ching-wan are (as one might expect) a delight in this -- and the rest of the cast is first-rate as well. The cinematography by CHENG Siu-kung is a bit offbeat (featuring almost fish-eye-ish distortion at times) but is as generally imaginative and stylish as is his norm. Yet another marvelous To film...

Sammi Cheng and LAU Ching-wan are (as one might expect) a delight in this -- and the rest of the cast is first-rate as well. The cinematography by CHENG Siu-kung is a bit offbeat (featuring almost fish-eye-ish distortion at times) but is as generally imaginative and stylish as is his norm. Yet another marvelous To film...

More screen captures:

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/to/eye/left02.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/to/eye/left03.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/to/eye/left04.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/to/eye/left05.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/to/eye/left08.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/to/eye/left09.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/to/eye/left12.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/to/eye/left13.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/to/eye/left14.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/to/eye/left15.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/to/eye/left16.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/to/eye/left18.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/to/eye/left19.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/to/eye/left20.png

Hokaibo -- Heisei Nakamura Za

Lincoln Center, July 21, 2007

The Japan society of Boston sponsored a one (long) day bus trip to New York City to see this kabuki play, which turned out to be a combination comedy-ghost story-romance-gore fest about a greedy and lascivious false priest. Great fun -- and a visual treat (especially in the third (and last) act. This was not your father kabuki performance -- but a very modern one (which paradoxically means it was true to the genuine traditions of kabuki).

According to JMDB, this was the fifty-fifth film Kinugasa directed (a number he would more than double by the time of his retirement in 1966). This is a somewhat less avant-garde silent film than Kinugasa's Kurutta ippeji (misnamed Page of Madness in English) from a couple of years earlier, but is still reasonably exotic looking. Mostly dark and brooding, with wildly exaggerated acting -- but presented in something approaching a linear fashion, with conventional intertitles. The basic scenario is simple a poor but honest young woman has a younger brother who has gotten himself into trouble due to his hopeless passion for a geisha -- and has also been blinded.

According to JMDB, this was the fifty-fifth film Kinugasa directed (a number he would more than double by the time of his retirement in 1966). This is a somewhat less avant-garde silent film than Kinugasa's Kurutta ippeji (misnamed Page of Madness in English) from a couple of years earlier, but is still reasonably exotic looking. Mostly dark and brooding, with wildly exaggerated acting -- but presented in something approaching a linear fashion, with conventional intertitles. The basic scenario is simple a poor but honest young woman has a younger brother who has gotten himself into trouble due to his hopeless passion for a geisha -- and has also been blinded.  Unscrupulous men try to take advantage of our heroine, using her brother's situation as leverage. He recovers his sight, and goes looking for the geisha and runs into more trouble, creating more unhappiness for his sister. The plot is wildly melodramatic and improbable -- and the cinematography is mostly dark and murky. The copy I saw of this was of poor quality, but I doubt even a better looking version would have won me over. Kinugasa, as director here, strikes me as erratic and haphazard -- as he does in his later films.

Unscrupulous men try to take advantage of our heroine, using her brother's situation as leverage. He recovers his sight, and goes looking for the geisha and runs into more trouble, creating more unhappiness for his sister. The plot is wildly melodramatic and improbable -- and the cinematography is mostly dark and murky. The copy I saw of this was of poor quality, but I doubt even a better looking version would have won me over. Kinugasa, as director here, strikes me as erratic and haphazard -- as he does in his later films.Dokkoi ikiteru / And Yet We Live (Tadashi Imai, 1951)

Another excellent Imai film about the plight of the under-privileged. This one deals with displaced workers in Tokyo, trying to earn enough to at least allow themselves and their families to scrape by. The primary focus is on a middle-aged father (Chojuro Kawarasaki) and mother (Hatae Kishi) with two young children. After they lose their shack of a home, Kawarasaki sends his family back to their home village and goes to live in a cheap worker's dormitory.

Another excellent Imai film about the plight of the under-privileged. This one deals with displaced workers in Tokyo, trying to earn enough to at least allow themselves and their families to scrape by. The primary focus is on a middle-aged father (Chojuro Kawarasaki) and mother (Hatae Kishi) with two young children. After they lose their shack of a home, Kawarasaki sends his family back to their home village and goes to live in a cheap worker's dormitory.  Elated when he finds a skilled factory job, he celebrates a bit too much with a shady old buddy (Kanemon Nakamura) and loses the money his old neighborhood friends have loaned him -- for his start at his new job. The job falls through and Kawarasaki goes back to seeking day labor work. Eventually, Nakamura convinces him to help with some illegal scavenger wotk (in a still bombed-out area of Tokyo), based on assurances that such activity was more profitable and entailed little risk. Of course, the two run into trouble.

Elated when he finds a skilled factory job, he celebrates a bit too much with a shady old buddy (Kanemon Nakamura) and loses the money his old neighborhood friends have loaned him -- for his start at his new job. The job falls through and Kawarasaki goes back to seeking day labor work. Eventually, Nakamura convinces him to help with some illegal scavenger wotk (in a still bombed-out area of Tokyo), based on assurances that such activity was more profitable and entailed little risk. Of course, the two run into trouble.  An ellipse finds Kawarasaki re-united with his family -- at the police station. With nowhere to live, the parents are at a loss. Kawarasaki's proposed solution is drastic, spend all they have on a nice day with the children (going to the zoo and having a picnic) followed by suicide for all. His wife continues to oppose the plan (quietly) but agrees to the outing. Late in the afternoon, fate intervenes -- as the couple's son almost drowns while playing with a dilapidated row boat (while the parents are preoccupied with their discussion). The last we see of the father, is his return to the day labor fray, albeit seemingly with a new sense of determination.

An ellipse finds Kawarasaki re-united with his family -- at the police station. With nowhere to live, the parents are at a loss. Kawarasaki's proposed solution is drastic, spend all they have on a nice day with the children (going to the zoo and having a picnic) followed by suicide for all. His wife continues to oppose the plan (quietly) but agrees to the outing. Late in the afternoon, fate intervenes -- as the couple's son almost drowns while playing with a dilapidated row boat (while the parents are preoccupied with their discussion). The last we see of the father, is his return to the day labor fray, albeit seemingly with a new sense of determination. Imai and his cinematographer Yoshio Miyajima (later a regular collaborator with Kobayashi) did a remarkable job of interweaving documentary-style footage with impeccably composed (yet none-the-less highly real looking) staged scenes. Comments on Imai's works of this sort invariably invoke the influence of post-war Italian neo-realism --

Imai and his cinematographer Yoshio Miyajima (later a regular collaborator with Kobayashi) did a remarkable job of interweaving documentary-style footage with impeccably composed (yet none-the-less highly real looking) staged scenes. Comments on Imai's works of this sort invariably invoke the influence of post-war Italian neo-realism --  and ignore Japan's own pre-war realist tradition (Shimizu, Uchida, Ozu, Yamanaka, Naruse et al.). The link with Yamanaka is especially striking -- as Kawarasaki and Nakamura (both former members of the same left-wing theatrical group) were the two lead actors in his Humanity and Paper Balloons. The rest of the cast, including youngster Isao Kimura and old-timer (and Ozu veteran) Choko Iida also do an excellent job of looking and acting like they were part of the extremely impoverished world the film portrays.

and ignore Japan's own pre-war realist tradition (Shimizu, Uchida, Ozu, Yamanaka, Naruse et al.). The link with Yamanaka is especially striking -- as Kawarasaki and Nakamura (both former members of the same left-wing theatrical group) were the two lead actors in his Humanity and Paper Balloons. The rest of the cast, including youngster Isao Kimura and old-timer (and Ozu veteran) Choko Iida also do an excellent job of looking and acting like they were part of the extremely impoverished world the film portrays. Like Uchida before him and Yamada after him, Imai was able to portray the plight of his less fortunate countryman with great sensitivity and without condescension -- while routinely exhibiting excellent visual sensibility. For reasons not entirely clear, most Western (or at least American) commentators have been fairly dismissive of the work of Imai. Apparently leftist sensibilities in makers of popular films (as opposed to avant-garde ones) was something that just was (and still is) not tolerable.

Like Uchida before him and Yamada after him, Imai was able to portray the plight of his less fortunate countryman with great sensitivity and without condescension -- while routinely exhibiting excellent visual sensibility. For reasons not entirely clear, most Western (or at least American) commentators have been fairly dismissive of the work of Imai. Apparently leftist sensibilities in makers of popular films (as opposed to avant-garde ones) was something that just was (and still is) not tolerable.More screenshots:

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/imai/dokko/yet03.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/imai/dokko/yet04.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/imai/dokko/yet06.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/imai/dokko/yet07.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/imai/dokko/yet09.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/imai/dokko/yet11.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/imai/dokko/yet12.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/imai/dokko/yet13.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/imai/dokko/yet14.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/imai/dokko/yet15.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/imai/dokko/yet16.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/imai/dokko/yet17.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/imai/dokko/yet18.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/imai/dokko/yet19.png

Soshun / Early Spring (Yasujiro Ozu, 1956)

In this mid-50s film, Ozu re-visits (for the last time) the world of the salaryman -- a topic near and dear to his heart in the 1930s. Although the economic climate of 50s Japan was decidedly better than that of twenty or so years earlier (when Japan was just edging out of a major depression), the picture Ozu paints of it is, in many ways, bleaker. Ozu is particularly interested here in the impact of the still-developing post-war "corporate culture" on Japanese family life.

In this mid-50s film, Ozu re-visits (for the last time) the world of the salaryman -- a topic near and dear to his heart in the 1930s. Although the economic climate of 50s Japan was decidedly better than that of twenty or so years earlier (when Japan was just edging out of a major depression), the picture Ozu paints of it is, in many ways, bleaker. Ozu is particularly interested here in the impact of the still-developing post-war "corporate culture" on Japanese family life.  Ryo Ikebe and Chikage Awashima have been married for about ten years -- and have gradually drifted apart since the death of their only child. Ikebe's focus has shifted more and more to work and to recreation after work with his colleagues from work, leaving Awashima with an increasing sense of futility. While her mother (Kumeko Urabe) counsels patience, Awashima finds her tolerance levels dropping. The situation worsens when Ikebe is drawn into a romance with a co-worker nicknamed Goldfish

Ryo Ikebe and Chikage Awashima have been married for about ten years -- and have gradually drifted apart since the death of their only child. Ikebe's focus has shifted more and more to work and to recreation after work with his colleagues from work, leaving Awashima with an increasing sense of futility. While her mother (Kumeko Urabe) counsels patience, Awashima finds her tolerance levels dropping. The situation worsens when Ikebe is drawn into a romance with a co-worker nicknamed Goldfish (Keiko Kishi). At around the time Ikebe is asked to "consider" a transfer to a provincial industrial city, Awashima decides she has had enough -- and moves in with her old school chum (Chieko Nakakita). Ikebe, unable to talk to his wife, moves to his new post alone. Along the way the way, he makes a visit to his mentor (Chishu Ryu) who was previously shunted off to a provincial assignment and (inexplicably, to his colleagues) has made no real push to return to the corporate rat race at the home office.

(Keiko Kishi). At around the time Ikebe is asked to "consider" a transfer to a provincial industrial city, Awashima decides she has had enough -- and moves in with her old school chum (Chieko Nakakita). Ikebe, unable to talk to his wife, moves to his new post alone. Along the way the way, he makes a visit to his mentor (Chishu Ryu) who was previously shunted off to a provincial assignment and (inexplicably, to his colleagues) has made no real push to return to the corporate rat race at the home office.  As it turns out, Ryu is pleased to have had the opportunity to spend more time with his wife and children -- and to repair the family relationships frayed by his over-busy professional life in Tokyo. Ryu urges Ikebe to similarly put his temporary posting to productive personal use -- and promises to try to help patch up things between Ikebe and Awashima. One day, on coming home to his rented apartment, Ikebe finds his wife has re-joined him -- and the two, both uncertain and hopeful, begin to think about their future.

As it turns out, Ryu is pleased to have had the opportunity to spend more time with his wife and children -- and to repair the family relationships frayed by his over-busy professional life in Tokyo. Ryu urges Ikebe to similarly put his temporary posting to productive personal use -- and promises to try to help patch up things between Ikebe and Awashima. One day, on coming home to his rented apartment, Ikebe finds his wife has re-joined him -- and the two, both uncertain and hopeful, begin to think about their future. Ozu's style here (with cinematography by Yuharu Atsuta) has become quite spare -- but their are still traces of camera movement here and there (some of these, traversing empty corridors briefly, are a bit mysterious). The over-riding tone is bleak -- and portions of the film are a bit seedy. A group hike (during which Ikebe and Kishi escape) offers a bit more liveliness, as do the comic interludes presided over by Urabe. But the over-riding tone is considerably more dour than Ozu's norm. It goes without saying that the performances (and script) are first rate. No, perhaps, one of Ozu's most easy to love films -- but one of considerable interest (despite its over two and a half hour length).

Ozu's style here (with cinematography by Yuharu Atsuta) has become quite spare -- but their are still traces of camera movement here and there (some of these, traversing empty corridors briefly, are a bit mysterious). The over-riding tone is bleak -- and portions of the film are a bit seedy. A group hike (during which Ikebe and Kishi escape) offers a bit more liveliness, as do the comic interludes presided over by Urabe. But the over-riding tone is considerably more dour than Ozu's norm. It goes without saying that the performances (and script) are first rate. No, perhaps, one of Ozu's most easy to love films -- but one of considerable interest (despite its over two and a half hour length).More pictures:

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/ozu/soshun03.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/ozu/soshun04.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/ozu/soshun05.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/ozu/soshun07.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/ozu/soshun08.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/ozu/soshun11.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/ozu/soshun12.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/ozu/soshun14.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/ozu/soshun15.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/ozu/soshun16.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/ozu/soshun17.png

Ngo joh aan gin diy gwai / My Left Eye Sees Ghosts (Johnnie To and WAI Ka-fai, 2002)

May (Sammi Cheng) falls in love with a rich young man (named Daniel) while on vacation and marries him -- but he dies soon afterward -- leaving his family and friends thinking she must simply be a lucky gold-digger. In fact, she is not able to shake off her grief -- and tries to commit suicide, but is saved by a ghost --

May (Sammi Cheng) falls in love with a rich young man (named Daniel) while on vacation and marries him -- but he dies soon afterward -- leaving his family and friends thinking she must simply be a lucky gold-digger. In fact, she is not able to shake off her grief -- and tries to commit suicide, but is saved by a ghost --  and afterwards she is able to see ghosts, but only with her left eye. With the aid of her father (LAM Suet), May determines that her rescuer ghost must be that of a childhood friend named Ken (LAU Ching-wan). Ken (having died young) tends to behave in a juvenile fashion --

and afterwards she is able to see ghosts, but only with her left eye. With the aid of her father (LAM Suet), May determines that her rescuer ghost must be that of a childhood friend named Ken (LAU Ching-wan). Ken (having died young) tends to behave in a juvenile fashion --  but clearly seems to have had a crush on May (and presumably still does). May has a number of problems -- with both ghosts and with the other females involved in the family business she inherited a part of (Daniel's mother and sister -- and Daniel's long-time, dumped friend). One thinks that the film will mostly be unalloyed silliness, then (as not uncommon), To and Wai shift gears -- and we move into deeper, more moving territory.

but clearly seems to have had a crush on May (and presumably still does). May has a number of problems -- with both ghosts and with the other females involved in the family business she inherited a part of (Daniel's mother and sister -- and Daniel's long-time, dumped friend). One thinks that the film will mostly be unalloyed silliness, then (as not uncommon), To and Wai shift gears -- and we move into deeper, more moving territory. Sammi Cheng and LAU Ching-wan are (as one might expect) a delight in this -- and the rest of the cast is first-rate as well. The cinematography by CHENG Siu-kung is a bit offbeat (featuring almost fish-eye-ish distortion at times) but is as generally imaginative and stylish as is his norm. Yet another marvelous To film...

Sammi Cheng and LAU Ching-wan are (as one might expect) a delight in this -- and the rest of the cast is first-rate as well. The cinematography by CHENG Siu-kung is a bit offbeat (featuring almost fish-eye-ish distortion at times) but is as generally imaginative and stylish as is his norm. Yet another marvelous To film...More screen captures:

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/to/eye/left02.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/to/eye/left03.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/to/eye/left04.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/to/eye/left05.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/to/eye/left08.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/to/eye/left09.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/to/eye/left12.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/to/eye/left13.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/to/eye/left14.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/to/eye/left15.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/to/eye/left16.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/to/eye/left18.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/to/eye/left19.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/to/eye/left20.png

Hokaibo -- Heisei Nakamura Za

Lincoln Center, July 21, 2007

The Japan society of Boston sponsored a one (long) day bus trip to New York City to see this kabuki play, which turned out to be a combination comedy-ghost story-romance-gore fest about a greedy and lascivious false priest. Great fun -- and a visual treat (especially in the third (and last) act. This was not your father kabuki performance -- but a very modern one (which paradoxically means it was true to the genuine traditions of kabuki).

Comments

I see this film as Ozu's response to Naruse's Repast. It covers a lot of similar territory, but explores it from a different perspective. One hint that Ozu might really be doing this is his choice of Kumeko Urabe to play his heroine's mother (the same functional role she played in Repast).