Watched July 23 - 29, 2007: -- Ozu and Kurosawa

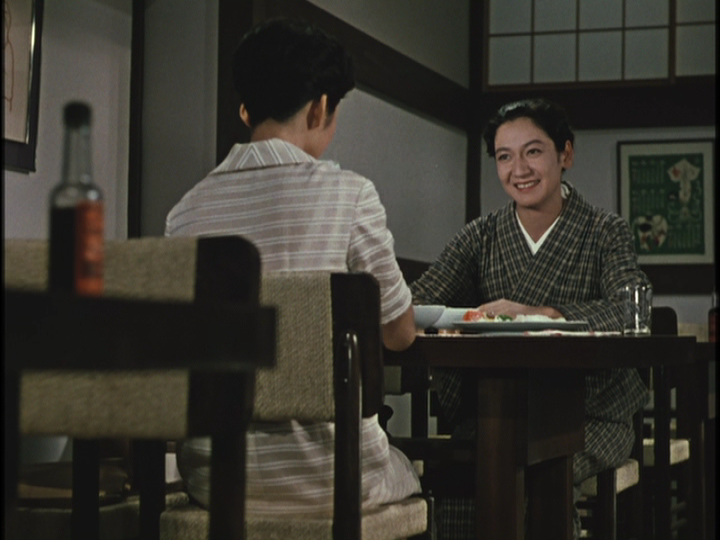

Akibiyori / Late Autumn (Yasujiro Ozu, 1960)

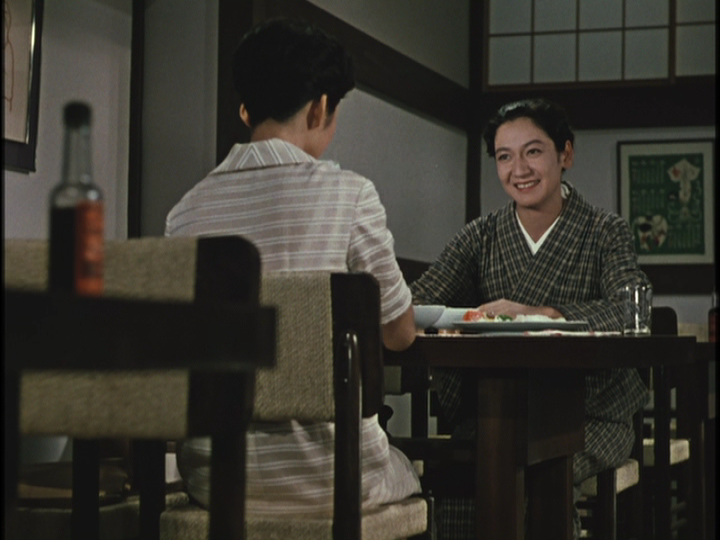

In this film, Ozu re-visits the theme of Late Spring, telling the story of a single parent and an only daughter. Here, however, Setsuko Hara plays the parent rather than the child (in one of the few roles where she played a character somewhat older than her real age). Her daughter (played by Yoko Tsukasa) is not strongly averse to marriage in principle -- but doesn't feel any urgency either. Nonetheless, as a lark (more or less), three of her late father's old buddies (Shin Saburi, Nobuo Nakamura and Ryuji KIta) decide to get her married off. When it turns out that she is reluctant to consider marriage due to concern over leaving her mother on her own, they also begin plotting to get her mother to re-marry. Ironically, they needn't have bothered, as Tsukasa meets someone (Keiji Sada)

Nonetheless, as a lark (more or less), three of her late father's old buddies (Shin Saburi, Nobuo Nakamura and Ryuji KIta) decide to get her married off. When it turns out that she is reluctant to consider marriage due to concern over leaving her mother on her own, they also begin plotting to get her mother to re-marry. Ironically, they needn't have bothered, as Tsukasa meets someone (Keiji Sada)  who catches her fancy through the good offices of one of her colleagues at work (who turns out to be the same person as Shin Saburi's proposed prospect). Their meddling manages to cause a breach between mother and daughter, prompting Tsukasa's friend (Mariko Okada) to put the three in their place. Ultimately, as the three codgers celebrate their "victory" after the wedding, Hara is left to deal with her unaccustomed loneliness.

who catches her fancy through the good offices of one of her colleagues at work (who turns out to be the same person as Shin Saburi's proposed prospect). Their meddling manages to cause a breach between mother and daughter, prompting Tsukasa's friend (Mariko Okada) to put the three in their place. Ultimately, as the three codgers celebrate their "victory" after the wedding, Hara is left to deal with her unaccustomed loneliness.

While this film has some (slightly) darker moments, until the very final scene, this appears to one of Ozu's lightest post-war domestic comedies. The three meddling geezers have a tendency to slip into adolescent humor -- and Okada's bearding of them in their own den (Saburi's office lounge) is one of Ozu's funniest scenes ever. What complicates the film is the fact that Hara's character, by and large, never finds much to laugh about in all the goings on.

While this film has some (slightly) darker moments, until the very final scene, this appears to one of Ozu's lightest post-war domestic comedies. The three meddling geezers have a tendency to slip into adolescent humor -- and Okada's bearding of them in their own den (Saburi's office lounge) is one of Ozu's funniest scenes ever. What complicates the film is the fact that Hara's character, by and large, never finds much to laugh about in all the goings on.  To be sure, she maintains her composure and her general good humor, but for all the humor at the center of the film, Hara (often on the periphery) remains a bit uneasy. Hara's performance here hints at the sort of actress she might have become if Ozu had not died just a couple of years later (and she not abruptly retired soon after Ozu's death). The rest of the cast is uniformly wonderful (as usual in Ozu).

To be sure, she maintains her composure and her general good humor, but for all the humor at the center of the film, Hara (often on the periphery) remains a bit uneasy. Hara's performance here hints at the sort of actress she might have become if Ozu had not died just a couple of years later (and she not abruptly retired soon after Ozu's death). The rest of the cast is uniformly wonderful (as usual in Ozu).

The new Eclipse DVD of this film is passable, but doesn't look as good as the unsubbed Shochiku DVD. It is well-subtitled, but -- like all other Eclipse releases -- has nothing in the way of extras.

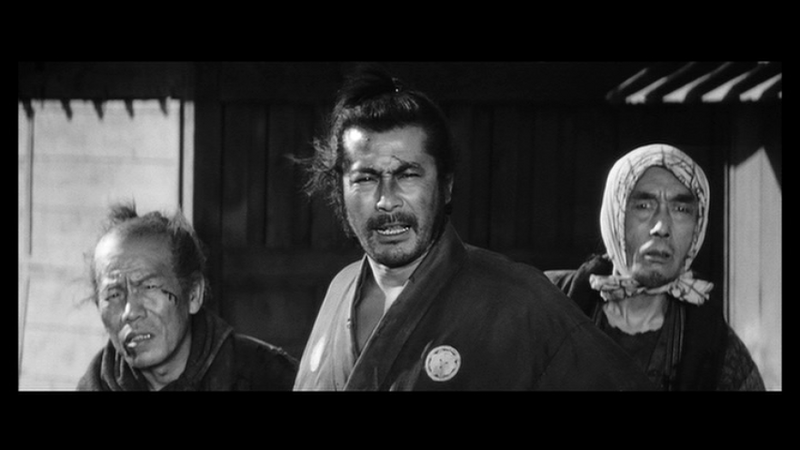

Yojimbo (Akira Kurosawa, 1961)

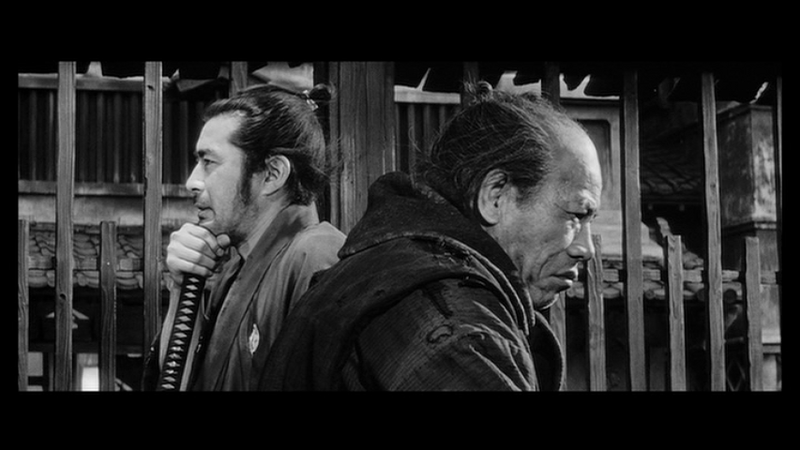

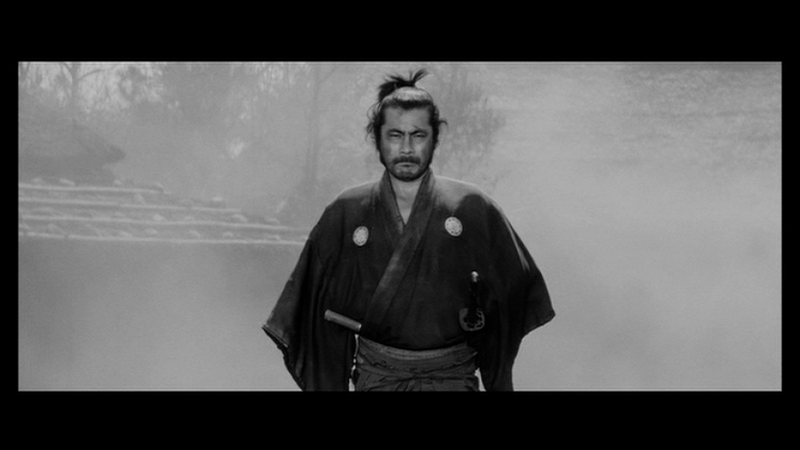

This film left me feeling more than a little ambivalent. It is unquestionably a gorgeous looking film, thanks to the cinematography of Kazuo Miyagawa and Takao Saitô (who was in charge of the telephoto work). And the near perpetual blowing wind and dust was also quite impressive.

This film left me feeling more than a little ambivalent. It is unquestionably a gorgeous looking film, thanks to the cinematography of Kazuo Miyagawa and Takao Saitô (who was in charge of the telephoto work). And the near perpetual blowing wind and dust was also quite impressive.  And there was a wonderful cast. But the thoroughgoing nihilistic cynicism that provided the thematic underpinning of the film was off-putting. Perhaps because of this sense of artistic estrangement, it dawned on me how ultimately elitist Kurosawa's vision typically is.

And there was a wonderful cast. But the thoroughgoing nihilistic cynicism that provided the thematic underpinning of the film was off-putting. Perhaps because of this sense of artistic estrangement, it dawned on me how ultimately elitist Kurosawa's vision typically is.

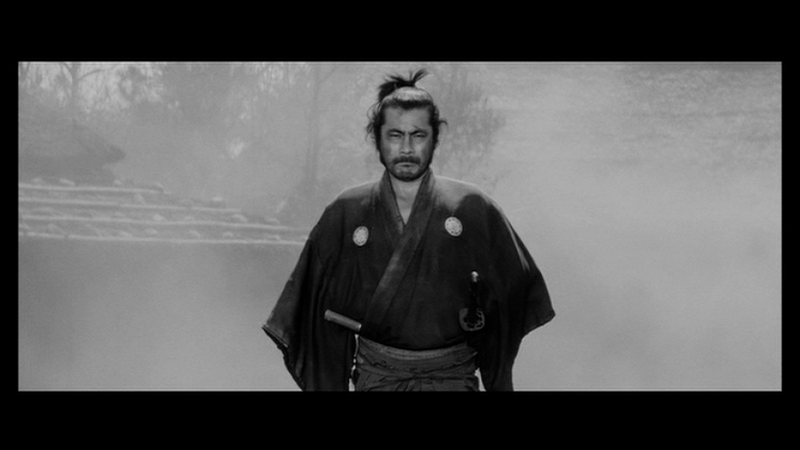

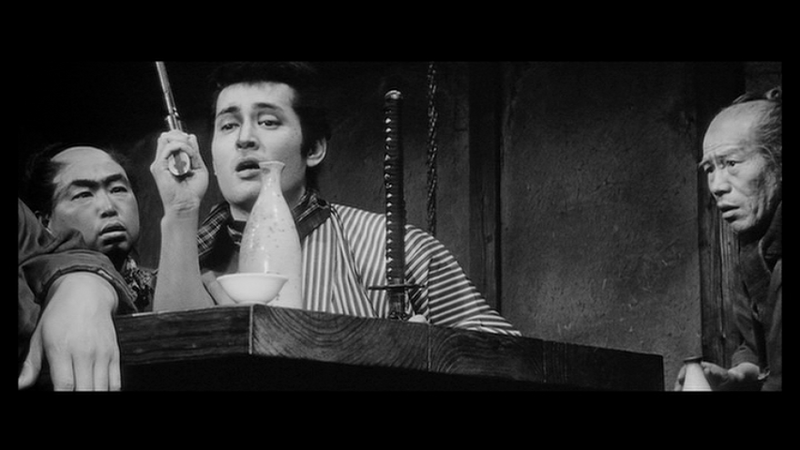

In this film, the protagonist (Sanjuro -- as embodied by Toshiro Mifune) doesn't really care about anyone. He pits the two ruling factions against each other, egging them on to destroy each other -- simply because he thinks the results will be "interesting". He does one apparent good deed, but it seems that this act is mainly there to provide an essential cog in the rather mechanistic plo

In this film, the protagonist (Sanjuro -- as embodied by Toshiro Mifune) doesn't really care about anyone. He pits the two ruling factions against each other, egging them on to destroy each other -- simply because he thinks the results will be "interesting". He does one apparent good deed, but it seems that this act is mainly there to provide an essential cog in the rather mechanistic plo t. He has no particular interest in "rescuing" the townsfolk from their thuggish overlords -- and, in fact, he leaves the town in a shambles at the end -- with its economic base almost totally wrecked. The central image of the film is Mifune, sitting in a tower, watching the mayhem and chuckling over the entertainment it provides him.

t. He has no particular interest in "rescuing" the townsfolk from their thuggish overlords -- and, in fact, he leaves the town in a shambles at the end -- with its economic base almost totally wrecked. The central image of the film is Mifune, sitting in a tower, watching the mayhem and chuckling over the entertainment it provides him.

On reflecting back on other Kurosawa films I have seen, it dawned on me that one could almost put Kurosawa up in that tower in place of his star. To be sure, Kurosawa normally exhibits a sort of good-natured "noblesse oblige" towards his poor and lower working class characters. But he rarely shows much in the way of identification with (or genuine interest in) their plight.

On reflecting back on other Kurosawa films I have seen, it dawned on me that one could almost put Kurosawa up in that tower in place of his star. To be sure, Kurosawa normally exhibits a sort of good-natured "noblesse oblige" towards his poor and lower working class characters. But he rarely shows much in the way of identification with (or genuine interest in) their plight.  While such characters may sometimes be "interesting"in an abstract fashion, they are routinely looked at as if from above (a point reflected literally in the cinematography of some of the films -- most notably in Lower Depths). In other films, peasant characters are viewed pretty explicitly as almost an alien species (see, for example, Seven Samurai). The characters he takes most interest in tend to belong to more valued social circles (even if they are poor and scruffy members of those circles).

While such characters may sometimes be "interesting"in an abstract fashion, they are routinely looked at as if from above (a point reflected literally in the cinematography of some of the films -- most notably in Lower Depths). In other films, peasant characters are viewed pretty explicitly as almost an alien species (see, for example, Seven Samurai). The characters he takes most interest in tend to belong to more valued social circles (even if they are poor and scruffy members of those circles).

In their early survey of Japanese cinema, Joseph Anderson and Donald Richie were quite enthusiastic about Kurosawa's work -- and almost uniformly dismissive of or (patronizing towards) any directors who seemed to take the situation of lower class characters too seriously (for example Tomu Uchida and Tadashi Imai). In more recent years, Richie hasn't really shifted from this sort of approach; in his most recent survey of Japanese cinema, he totally ignored the work of Yoji Yamada, one of Japan's most successful directors for more than three decades.

In their early survey of Japanese cinema, Joseph Anderson and Donald Richie were quite enthusiastic about Kurosawa's work -- and almost uniformly dismissive of or (patronizing towards) any directors who seemed to take the situation of lower class characters too seriously (for example Tomu Uchida and Tadashi Imai). In more recent years, Richie hasn't really shifted from this sort of approach; in his most recent survey of Japanese cinema, he totally ignored the work of Yoji Yamada, one of Japan's most successful directors for more than three decades.  Like Uchida and Imai, Yamada routinely treats the concerns of those near the bottom of the socioeconomic pyramid as important -- and views the lowliest of his characters as worthy of respect. Clearly the preferences of Anderson and Richie reflected those of their American audience. While Uchida and Imai got some attention in both the United States and Europe back in the 50s and early 60s, their "leftist" films totally disappeared from the English-speaking world ages ago. Similarly, even the best films of Yoji Yamada, for all their popularity throughout Asia, have never really got much traction in the United States.

Like Uchida and Imai, Yamada routinely treats the concerns of those near the bottom of the socioeconomic pyramid as important -- and views the lowliest of his characters as worthy of respect. Clearly the preferences of Anderson and Richie reflected those of their American audience. While Uchida and Imai got some attention in both the United States and Europe back in the 50s and early 60s, their "leftist" films totally disappeared from the English-speaking world ages ago. Similarly, even the best films of Yoji Yamada, for all their popularity throughout Asia, have never really got much traction in the United States.

Returning to Yojimbo, I would note that the new Criterion DVD of the film looks wonderful. And the primary extra of the set, the installment of It's Wonderful to Create devoted to Yojimbo, is extremely informative and enjoyable.

Returning to Yojimbo, I would note that the new Criterion DVD of the film looks wonderful. And the primary extra of the set, the installment of It's Wonderful to Create devoted to Yojimbo, is extremely informative and enjoyable.

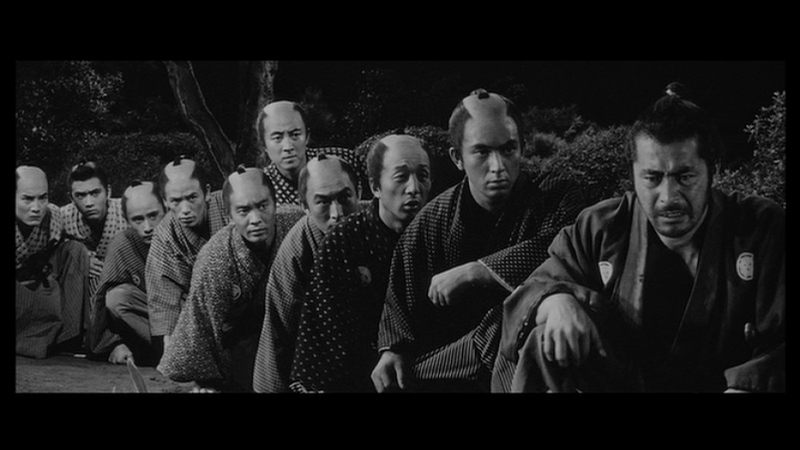

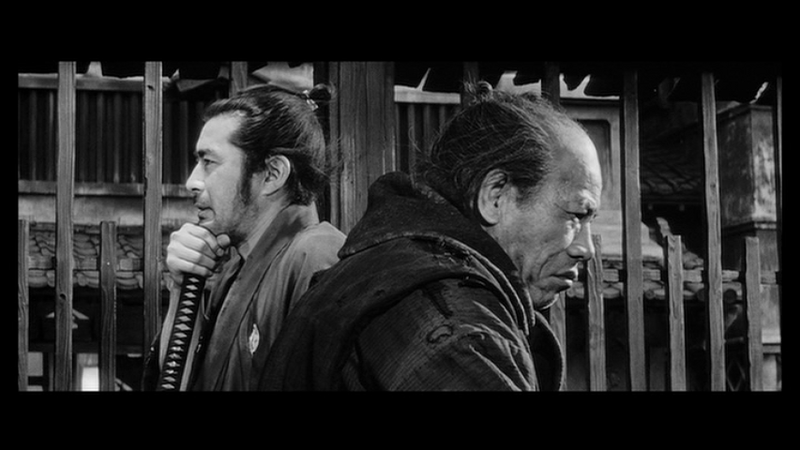

Tsubaki Sanjûrô / Sanjuro (Akira Kurosawa, 1962)

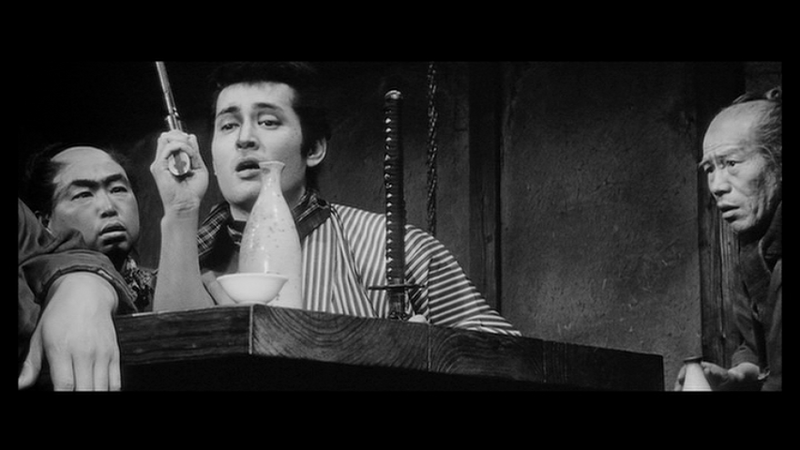

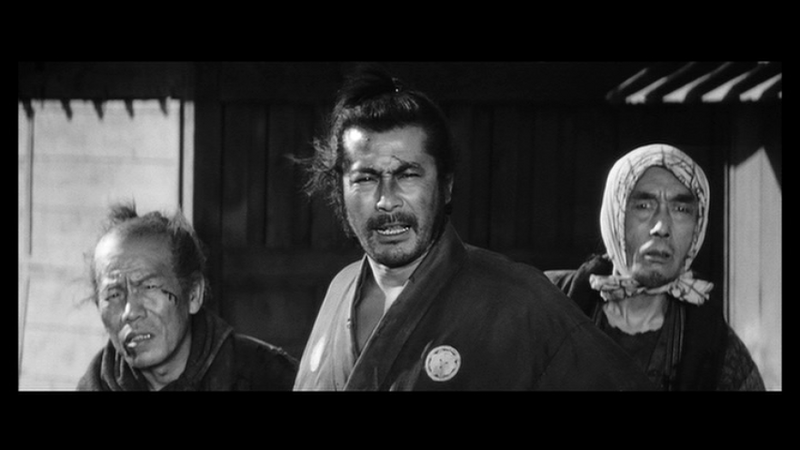

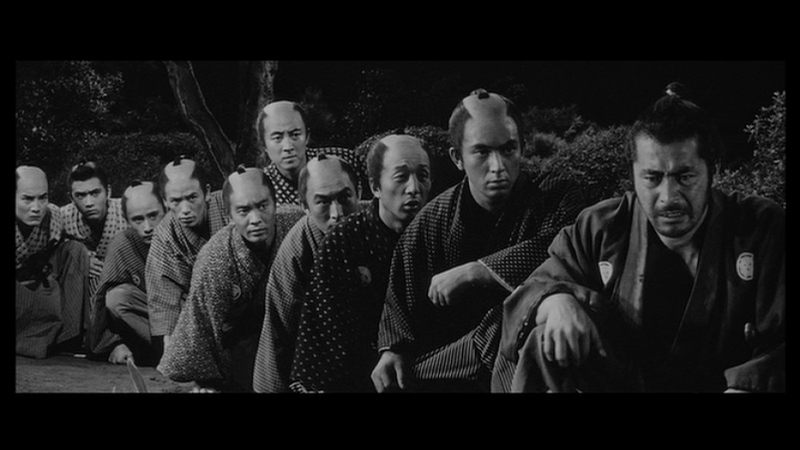

If ordinary townsfolk were largely invisible in Yojimbo, they disappear almost entirely in Sanjuro. The entire cast seems to be made up of members of the samurai class. Once again, Sanjuro (Mifune) has walked into a hornet's nest of sorts. A bunch of idealistic young samurai have discovered corruption in their clan,

If ordinary townsfolk were largely invisible in Yojimbo, they disappear almost entirely in Sanjuro. The entire cast seems to be made up of members of the samurai class. Once again, Sanjuro (Mifune) has walked into a hornet's nest of sorts. A bunch of idealistic young samurai have discovered corruption in their clan,  but their attempts to deal with it have proved to be potentially disastrous. Misled by slickness, they have actually tipped off the bad guys (Takashi Shimura, Tatsuya Nakadai et al), putting the good guys (Yûnosuke Itô, Takako Irie, Reiko Dan and themselves) in danger. Out of a sense of frustration, perhaps, Sanjuro decides to try to help the inept do-gooders out of the mess they created.

but their attempts to deal with it have proved to be potentially disastrous. Misled by slickness, they have actually tipped off the bad guys (Takashi Shimura, Tatsuya Nakadai et al), putting the good guys (Yûnosuke Itô, Takako Irie, Reiko Dan and themselves) in danger. Out of a sense of frustration, perhaps, Sanjuro decides to try to help the inept do-gooders out of the mess they created.

This film has a far more good-natured and easy-going tone than Yojimbo -- and one can actually like some of the characters here. Takako Irie, as the elderly wife of the endangered official, is especially amiable -- with her complacency in the face of disaster and her ability to see through Sanjuro.

This film has a far more good-natured and easy-going tone than Yojimbo -- and one can actually like some of the characters here. Takako Irie, as the elderly wife of the endangered official, is especially amiable -- with her complacency in the face of disaster and her ability to see through Sanjuro.  Keiju Kobayashi (a perennial nice guy in Naruse's films) appears as a captured "enemy" who blithely switches sides when he discovers the truth of what has been going on. In the It's Wonderful to Create installment for this film, Kobayashi tells us that Kurosawa allowed him to improvise large parts of his role (and associated dialog).

Keiju Kobayashi (a perennial nice guy in Naruse's films) appears as a captured "enemy" who blithely switches sides when he discovers the truth of what has been going on. In the It's Wonderful to Create installment for this film, Kobayashi tells us that Kurosawa allowed him to improvise large parts of his role (and associated dialog).

The cinematography here is good enough, but generally lacks the superabundant stylishness provided by Miyagawa in Yojimbo. The DVD looks good too -- but not as strikingly so as its companion film. Not as "important" a film as Yojimbo, perhaps, but one a lot more entertaining to watch. All the same, neither of these films equals Sadao Yamanaka's three surviving films from the 1930s or Uchida's 1955 Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji.

The cinematography here is good enough, but generally lacks the superabundant stylishness provided by Miyagawa in Yojimbo. The DVD looks good too -- but not as strikingly so as its companion film. Not as "important" a film as Yojimbo, perhaps, but one a lot more entertaining to watch. All the same, neither of these films equals Sadao Yamanaka's three surviving films from the 1930s or Uchida's 1955 Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji.

In this film, Ozu re-visits the theme of Late Spring, telling the story of a single parent and an only daughter. Here, however, Setsuko Hara plays the parent rather than the child (in one of the few roles where she played a character somewhat older than her real age). Her daughter (played by Yoko Tsukasa) is not strongly averse to marriage in principle -- but doesn't feel any urgency either.

Nonetheless, as a lark (more or less), three of her late father's old buddies (Shin Saburi, Nobuo Nakamura and Ryuji KIta) decide to get her married off. When it turns out that she is reluctant to consider marriage due to concern over leaving her mother on her own, they also begin plotting to get her mother to re-marry. Ironically, they needn't have bothered, as Tsukasa meets someone (Keiji Sada)

Nonetheless, as a lark (more or less), three of her late father's old buddies (Shin Saburi, Nobuo Nakamura and Ryuji KIta) decide to get her married off. When it turns out that she is reluctant to consider marriage due to concern over leaving her mother on her own, they also begin plotting to get her mother to re-marry. Ironically, they needn't have bothered, as Tsukasa meets someone (Keiji Sada)  who catches her fancy through the good offices of one of her colleagues at work (who turns out to be the same person as Shin Saburi's proposed prospect). Their meddling manages to cause a breach between mother and daughter, prompting Tsukasa's friend (Mariko Okada) to put the three in their place. Ultimately, as the three codgers celebrate their "victory" after the wedding, Hara is left to deal with her unaccustomed loneliness.

who catches her fancy through the good offices of one of her colleagues at work (who turns out to be the same person as Shin Saburi's proposed prospect). Their meddling manages to cause a breach between mother and daughter, prompting Tsukasa's friend (Mariko Okada) to put the three in their place. Ultimately, as the three codgers celebrate their "victory" after the wedding, Hara is left to deal with her unaccustomed loneliness. While this film has some (slightly) darker moments, until the very final scene, this appears to one of Ozu's lightest post-war domestic comedies. The three meddling geezers have a tendency to slip into adolescent humor -- and Okada's bearding of them in their own den (Saburi's office lounge) is one of Ozu's funniest scenes ever. What complicates the film is the fact that Hara's character, by and large, never finds much to laugh about in all the goings on.

While this film has some (slightly) darker moments, until the very final scene, this appears to one of Ozu's lightest post-war domestic comedies. The three meddling geezers have a tendency to slip into adolescent humor -- and Okada's bearding of them in their own den (Saburi's office lounge) is one of Ozu's funniest scenes ever. What complicates the film is the fact that Hara's character, by and large, never finds much to laugh about in all the goings on.  To be sure, she maintains her composure and her general good humor, but for all the humor at the center of the film, Hara (often on the periphery) remains a bit uneasy. Hara's performance here hints at the sort of actress she might have become if Ozu had not died just a couple of years later (and she not abruptly retired soon after Ozu's death). The rest of the cast is uniformly wonderful (as usual in Ozu).

To be sure, she maintains her composure and her general good humor, but for all the humor at the center of the film, Hara (often on the periphery) remains a bit uneasy. Hara's performance here hints at the sort of actress she might have become if Ozu had not died just a couple of years later (and she not abruptly retired soon after Ozu's death). The rest of the cast is uniformly wonderful (as usual in Ozu).The new Eclipse DVD of this film is passable, but doesn't look as good as the unsubbed Shochiku DVD. It is well-subtitled, but -- like all other Eclipse releases -- has nothing in the way of extras.

Yojimbo (Akira Kurosawa, 1961)

This film left me feeling more than a little ambivalent. It is unquestionably a gorgeous looking film, thanks to the cinematography of Kazuo Miyagawa and Takao Saitô (who was in charge of the telephoto work). And the near perpetual blowing wind and dust was also quite impressive.

This film left me feeling more than a little ambivalent. It is unquestionably a gorgeous looking film, thanks to the cinematography of Kazuo Miyagawa and Takao Saitô (who was in charge of the telephoto work). And the near perpetual blowing wind and dust was also quite impressive.  And there was a wonderful cast. But the thoroughgoing nihilistic cynicism that provided the thematic underpinning of the film was off-putting. Perhaps because of this sense of artistic estrangement, it dawned on me how ultimately elitist Kurosawa's vision typically is.

And there was a wonderful cast. But the thoroughgoing nihilistic cynicism that provided the thematic underpinning of the film was off-putting. Perhaps because of this sense of artistic estrangement, it dawned on me how ultimately elitist Kurosawa's vision typically is.  In this film, the protagonist (Sanjuro -- as embodied by Toshiro Mifune) doesn't really care about anyone. He pits the two ruling factions against each other, egging them on to destroy each other -- simply because he thinks the results will be "interesting". He does one apparent good deed, but it seems that this act is mainly there to provide an essential cog in the rather mechanistic plo

In this film, the protagonist (Sanjuro -- as embodied by Toshiro Mifune) doesn't really care about anyone. He pits the two ruling factions against each other, egging them on to destroy each other -- simply because he thinks the results will be "interesting". He does one apparent good deed, but it seems that this act is mainly there to provide an essential cog in the rather mechanistic plo t. He has no particular interest in "rescuing" the townsfolk from their thuggish overlords -- and, in fact, he leaves the town in a shambles at the end -- with its economic base almost totally wrecked. The central image of the film is Mifune, sitting in a tower, watching the mayhem and chuckling over the entertainment it provides him.

t. He has no particular interest in "rescuing" the townsfolk from their thuggish overlords -- and, in fact, he leaves the town in a shambles at the end -- with its economic base almost totally wrecked. The central image of the film is Mifune, sitting in a tower, watching the mayhem and chuckling over the entertainment it provides him. On reflecting back on other Kurosawa films I have seen, it dawned on me that one could almost put Kurosawa up in that tower in place of his star. To be sure, Kurosawa normally exhibits a sort of good-natured "noblesse oblige" towards his poor and lower working class characters. But he rarely shows much in the way of identification with (or genuine interest in) their plight.

On reflecting back on other Kurosawa films I have seen, it dawned on me that one could almost put Kurosawa up in that tower in place of his star. To be sure, Kurosawa normally exhibits a sort of good-natured "noblesse oblige" towards his poor and lower working class characters. But he rarely shows much in the way of identification with (or genuine interest in) their plight.  While such characters may sometimes be "interesting"in an abstract fashion, they are routinely looked at as if from above (a point reflected literally in the cinematography of some of the films -- most notably in Lower Depths). In other films, peasant characters are viewed pretty explicitly as almost an alien species (see, for example, Seven Samurai). The characters he takes most interest in tend to belong to more valued social circles (even if they are poor and scruffy members of those circles).

While such characters may sometimes be "interesting"in an abstract fashion, they are routinely looked at as if from above (a point reflected literally in the cinematography of some of the films -- most notably in Lower Depths). In other films, peasant characters are viewed pretty explicitly as almost an alien species (see, for example, Seven Samurai). The characters he takes most interest in tend to belong to more valued social circles (even if they are poor and scruffy members of those circles).  In their early survey of Japanese cinema, Joseph Anderson and Donald Richie were quite enthusiastic about Kurosawa's work -- and almost uniformly dismissive of or (patronizing towards) any directors who seemed to take the situation of lower class characters too seriously (for example Tomu Uchida and Tadashi Imai). In more recent years, Richie hasn't really shifted from this sort of approach; in his most recent survey of Japanese cinema, he totally ignored the work of Yoji Yamada, one of Japan's most successful directors for more than three decades.

In their early survey of Japanese cinema, Joseph Anderson and Donald Richie were quite enthusiastic about Kurosawa's work -- and almost uniformly dismissive of or (patronizing towards) any directors who seemed to take the situation of lower class characters too seriously (for example Tomu Uchida and Tadashi Imai). In more recent years, Richie hasn't really shifted from this sort of approach; in his most recent survey of Japanese cinema, he totally ignored the work of Yoji Yamada, one of Japan's most successful directors for more than three decades.  Like Uchida and Imai, Yamada routinely treats the concerns of those near the bottom of the socioeconomic pyramid as important -- and views the lowliest of his characters as worthy of respect. Clearly the preferences of Anderson and Richie reflected those of their American audience. While Uchida and Imai got some attention in both the United States and Europe back in the 50s and early 60s, their "leftist" films totally disappeared from the English-speaking world ages ago. Similarly, even the best films of Yoji Yamada, for all their popularity throughout Asia, have never really got much traction in the United States.

Like Uchida and Imai, Yamada routinely treats the concerns of those near the bottom of the socioeconomic pyramid as important -- and views the lowliest of his characters as worthy of respect. Clearly the preferences of Anderson and Richie reflected those of their American audience. While Uchida and Imai got some attention in both the United States and Europe back in the 50s and early 60s, their "leftist" films totally disappeared from the English-speaking world ages ago. Similarly, even the best films of Yoji Yamada, for all their popularity throughout Asia, have never really got much traction in the United States. Returning to Yojimbo, I would note that the new Criterion DVD of the film looks wonderful. And the primary extra of the set, the installment of It's Wonderful to Create devoted to Yojimbo, is extremely informative and enjoyable.

Returning to Yojimbo, I would note that the new Criterion DVD of the film looks wonderful. And the primary extra of the set, the installment of It's Wonderful to Create devoted to Yojimbo, is extremely informative and enjoyable.Tsubaki Sanjûrô / Sanjuro (Akira Kurosawa, 1962)

If ordinary townsfolk were largely invisible in Yojimbo, they disappear almost entirely in Sanjuro. The entire cast seems to be made up of members of the samurai class. Once again, Sanjuro (Mifune) has walked into a hornet's nest of sorts. A bunch of idealistic young samurai have discovered corruption in their clan,

If ordinary townsfolk were largely invisible in Yojimbo, they disappear almost entirely in Sanjuro. The entire cast seems to be made up of members of the samurai class. Once again, Sanjuro (Mifune) has walked into a hornet's nest of sorts. A bunch of idealistic young samurai have discovered corruption in their clan,  but their attempts to deal with it have proved to be potentially disastrous. Misled by slickness, they have actually tipped off the bad guys (Takashi Shimura, Tatsuya Nakadai et al), putting the good guys (Yûnosuke Itô, Takako Irie, Reiko Dan and themselves) in danger. Out of a sense of frustration, perhaps, Sanjuro decides to try to help the inept do-gooders out of the mess they created.

but their attempts to deal with it have proved to be potentially disastrous. Misled by slickness, they have actually tipped off the bad guys (Takashi Shimura, Tatsuya Nakadai et al), putting the good guys (Yûnosuke Itô, Takako Irie, Reiko Dan and themselves) in danger. Out of a sense of frustration, perhaps, Sanjuro decides to try to help the inept do-gooders out of the mess they created.  This film has a far more good-natured and easy-going tone than Yojimbo -- and one can actually like some of the characters here. Takako Irie, as the elderly wife of the endangered official, is especially amiable -- with her complacency in the face of disaster and her ability to see through Sanjuro.

This film has a far more good-natured and easy-going tone than Yojimbo -- and one can actually like some of the characters here. Takako Irie, as the elderly wife of the endangered official, is especially amiable -- with her complacency in the face of disaster and her ability to see through Sanjuro.  Keiju Kobayashi (a perennial nice guy in Naruse's films) appears as a captured "enemy" who blithely switches sides when he discovers the truth of what has been going on. In the It's Wonderful to Create installment for this film, Kobayashi tells us that Kurosawa allowed him to improvise large parts of his role (and associated dialog).

Keiju Kobayashi (a perennial nice guy in Naruse's films) appears as a captured "enemy" who blithely switches sides when he discovers the truth of what has been going on. In the It's Wonderful to Create installment for this film, Kobayashi tells us that Kurosawa allowed him to improvise large parts of his role (and associated dialog). The cinematography here is good enough, but generally lacks the superabundant stylishness provided by Miyagawa in Yojimbo. The DVD looks good too -- but not as strikingly so as its companion film. Not as "important" a film as Yojimbo, perhaps, but one a lot more entertaining to watch. All the same, neither of these films equals Sadao Yamanaka's three surviving films from the 1930s or Uchida's 1955 Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji.

The cinematography here is good enough, but generally lacks the superabundant stylishness provided by Miyagawa in Yojimbo. The DVD looks good too -- but not as strikingly so as its companion film. Not as "important" a film as Yojimbo, perhaps, but one a lot more entertaining to watch. All the same, neither of these films equals Sadao Yamanaka's three surviving films from the 1930s or Uchida's 1955 Bloody Spear at Mount Fuji.

Comments

Victor Enyutin