Watched November 5 - 11, 2007: Eisenstein, Shimizu, Ozu and Godard

Bronenosets Potyomkin / Battleship Potemkin (Sergei M. Eisenstein, 1925)

I first saw this film around 35 years ago -- at a college screening. This screening is also notable for being the only time I stood up and told a bunch of obnoxious noisemakers to shut up and let the rest of the audience experience the film without the "benefit" of their running commentary.

I first saw this film around 35 years ago -- at a college screening. This screening is also notable for being the only time I stood up and told a bunch of obnoxious noisemakers to shut up and let the rest of the audience experience the film without the "benefit" of their running commentary.  At this remote date, I can't recall what musical score this print used -- but I would assume that it was the 1950s version by Nikolai Kryukov. Subsequent viewings (on video and DVD) all utilized a score cobbled together by bits and pieces of Shostakovich works.

At this remote date, I can't recall what musical score this print used -- but I would assume that it was the 1950s version by Nikolai Kryukov. Subsequent viewings (on video and DVD) all utilized a score cobbled together by bits and pieces of Shostakovich works.  Now, at last, there is a restored version that uses the first music composed for the film -- by Edmund Meisel. Although a big fan of Shostakovich in general, I never felt the music borrowed from him fit the film as well as it should. So my main interest in the new DVD (from Kino) was the score.

Now, at last, there is a restored version that uses the first music composed for the film -- by Edmund Meisel. Although a big fan of Shostakovich in general, I never felt the music borrowed from him fit the film as well as it should. So my main interest in the new DVD (from Kino) was the score.

As it turns out, Meisel's score (which makes lots of use of the melodies of revolutionary songs from the period in which the film was set) was very effective. But, though I had always been

As it turns out, Meisel's score (which makes lots of use of the melodies of revolutionary songs from the period in which the film was set) was very effective. But, though I had always been  (reasonably) satisfied by the visual quality of my prior DVD, I found the improvement in the image quality in this new release equally striking. For all practical purposes, I find it hard to imagine that this new DVD is likely to be bettered anytime in the foreseeable future.

(reasonably) satisfied by the visual quality of my prior DVD, I found the improvement in the image quality in this new release equally striking. For all practical purposes, I find it hard to imagine that this new DVD is likely to be bettered anytime in the foreseeable future.

Arigato-san / Mr. Thank You (Hiroshi Shimizu, 1936)

Alas, no one has ever bothered (yet) to do any DVD release (even unsubtitled) of Shimizu's remarkable chronicle of an ordinary rural bus ride. Filmed almost entirely in (and around) a small bus, as it actually traveled rural roads, this film uncannily anticipates the much later work of directors (like Kiarostami). The film is aggressively limited to the present -- we not only see nothing of the past, we hear virtually nothing about it in the conversations that take place.

Alas, no one has ever bothered (yet) to do any DVD release (even unsubtitled) of Shimizu's remarkable chronicle of an ordinary rural bus ride. Filmed almost entirely in (and around) a small bus, as it actually traveled rural roads, this film uncannily anticipates the much later work of directors (like Kiarostami). The film is aggressively limited to the present -- we not only see nothing of the past, we hear virtually nothing about it in the conversations that take place.

The primary cast of character here consists of a good-natured (and good-looking) young bus drive (Ken Uehara), a despondent teenager (Mayumi Tsukiji) and her mother, a fusty old businessman and another young woman (Michiko Kuwano), more sophisticated than the first, but probably not a great deal older.

The primary cast of character here consists of a good-natured (and good-looking) young bus drive (Ken Uehara), a despondent teenager (Mayumi Tsukiji) and her mother, a fusty old businessman and another young woman (Michiko Kuwano), more sophisticated than the first, but probably not a great deal older.  Uehara is called Arigato-san because of his unfailing courtesy as he drives his route -- and he seems to know almost everyone he encounters along the way. Kuwano, dressed in the latest fashions, is clearly interested in Uehara --

Uehara is called Arigato-san because of his unfailing courtesy as he drives his route -- and he seems to know almost everyone he encounters along the way. Kuwano, dressed in the latest fashions, is clearly interested in Uehara --  but he seems to be more intrigued by the sad (kimono-clad) young woman sitting in the back. As it turns out, she is on her way to Tokyo for the purpose of being (for all practical purposes) sold into sexual slavery, due to the destitution of her family. Her chatty mother seems to be willing to talk about their errand -- but the girl, ashamed, doesn't want the topic discussed. T

but he seems to be more intrigued by the sad (kimono-clad) young woman sitting in the back. As it turns out, she is on her way to Tokyo for the purpose of being (for all practical purposes) sold into sexual slavery, due to the destitution of her family. Her chatty mother seems to be willing to talk about their errand -- but the girl, ashamed, doesn't want the topic discussed. T he businessman's main function seems to be as a target for the modern girl's barbs. Meanwhile the driver maintains his composure and sunny disposition, sometimes stopping to chat with people he encounters (especially when they are young and pretty women -- like a pair of traveling musicians and a Korean migrant worker).

he businessman's main function seems to be as a target for the modern girl's barbs. Meanwhile the driver maintains his composure and sunny disposition, sometimes stopping to chat with people he encounters (especially when they are young and pretty women -- like a pair of traveling musicians and a Korean migrant worker).

While the modern girl says almost nothing about her own activities and livelihood, it gradually becomes clear that she may well have been in the same situation as her younger "rival" just a few years earlier. As the journey goes on, her effervescence begins to wane, as the the younger woman slowly (and shyly) begins to take notice of the driver.

While the modern girl says almost nothing about her own activities and livelihood, it gradually becomes clear that she may well have been in the same situation as her younger "rival" just a few years earlier. As the journey goes on, her effervescence begins to wane, as the the younger woman slowly (and shyly) begins to take notice of the driver.  Shimizu shows great sympathy to not only these two main heroines, but also to the Korean girl -- who has served as part of a road repair crew (along with her family and other impoverished Koreans) but now must travel (on foot) to a distant part of Japan for her next project. At least during this era, Shimizu might be unique in his expression of open sympathy (here and elsewhere) for foreigners subject to economic oppression and/or prejudice.

Shimizu shows great sympathy to not only these two main heroines, but also to the Korean girl -- who has served as part of a road repair crew (along with her family and other impoverished Koreans) but now must travel (on foot) to a distant part of Japan for her next project. At least during this era, Shimizu might be unique in his expression of open sympathy (here and elsewhere) for foreigners subject to economic oppression and/or prejudice.

Apparently there is a nice looking subtitled print of this film, but my exposure has been limited to (first) a very bad looking copy of a television broadcast and (now) a much better (but still not quite satisfactory) copy of a more recent Japanese broadcast. Assuming one is able to enjoy "plotless" Asian films, this film should be considered a "don't miss" if it is shown anywhere reachable -- or eventually becomes available on DVD.

Apparently there is a nice looking subtitled print of this film, but my exposure has been limited to (first) a very bad looking copy of a television broadcast and (now) a much better (but still not quite satisfactory) copy of a more recent Japanese broadcast. Assuming one is able to enjoy "plotless" Asian films, this film should be considered a "don't miss" if it is shown anywhere reachable -- or eventually becomes available on DVD.

Tôkyô boshoku / Tokyo Twilight (Yasujiro Ozu, 1957)

When I first watched Tokyo Twilight back in 2001 (courtesy of a now long out of print French video), the film was routinely written off in the English-speaking world as failure -- consistent with the almost uniform rejection of the film by both Japanese critics and audiences at the time of its initial release. While Ozu normally shrugged off problems of this sort (fortunately rare), he apparently was greatly distressed by the poor reception this film received (according to Masahiro Shinoda, then an assistant director working with Ozu).

When I first watched Tokyo Twilight back in 2001 (courtesy of a now long out of print French video), the film was routinely written off in the English-speaking world as failure -- consistent with the almost uniform rejection of the film by both Japanese critics and audiences at the time of its initial release. While Ozu normally shrugged off problems of this sort (fortunately rare), he apparently was greatly distressed by the poor reception this film received (according to Masahiro Shinoda, then an assistant director working with Ozu).  The fact that he had been cautioned in advance by his co-writer Kogo Noda, did not lessen his disappointment. Only a few voices, over the years, offered an alternate view. Donald Richie recognized the fact that Ozu had moved (courageously) into remarkably dark territory in this film -- and Japanese scholar Shigehiko Hasumi pointed out both the value of the film and the importance of factoring it into any comprehensive evaluation of Ozu's work.

The fact that he had been cautioned in advance by his co-writer Kogo Noda, did not lessen his disappointment. Only a few voices, over the years, offered an alternate view. Donald Richie recognized the fact that Ozu had moved (courageously) into remarkably dark territory in this film -- and Japanese scholar Shigehiko Hasumi pointed out both the value of the film and the importance of factoring it into any comprehensive evaluation of Ozu's work.  Unfortunately, Hasumi's comments of Tokyo Twilight never made it into English (while the chapter in his Ozu book that discussed this film was published in translation, virtually all discussion of it was omitted). Only with the widely-traveled 2003 Ozu retrospective (in honor of his hundredth birthday), has there been a critical reappraisal of this long neglected film -- and the dawning of an awareness (almost 50 years after its premiere) that this "flop" might actually be a masterpiece.

Unfortunately, Hasumi's comments of Tokyo Twilight never made it into English (while the chapter in his Ozu book that discussed this film was published in translation, virtually all discussion of it was omitted). Only with the widely-traveled 2003 Ozu retrospective (in honor of his hundredth birthday), has there been a critical reappraisal of this long neglected film -- and the dawning of an awareness (almost 50 years after its premiere) that this "flop" might actually be a masterpiece.

Why, one wonders, was the initial reaction to this film so hostile? The answer is probably not too hard to discern. First of all, Ozu dared to have his most universally beloved performers, Chishu Ryu and Setsuko Hara, play roles that were like dark inversions of their normal characters -- not "evil" characters, but deeply flawed ones who ultimately cause a great deal of harm. The single father Ryu plays here is oblivious and inept. Hara plays his eldest daughter, who he previously pushed into a fairly disastrous marriage, and who has just moved back home (with her young child), finding life with her abusive husband intolerable.

Why, one wonders, was the initial reaction to this film so hostile? The answer is probably not too hard to discern. First of all, Ozu dared to have his most universally beloved performers, Chishu Ryu and Setsuko Hara, play roles that were like dark inversions of their normal characters -- not "evil" characters, but deeply flawed ones who ultimately cause a great deal of harm. The single father Ryu plays here is oblivious and inept. Hara plays his eldest daughter, who he previously pushed into a fairly disastrous marriage, and who has just moved back home (with her young child), finding life with her abusive husband intolerable.  Ryu's younger daughter, played by Ineko Arima, is an unhappy individual clearly in serious trouble, with no one to turn to. Into this volatile situation, Ozu throws a match -- the return of Ryu's divorced wife (who abandoned -- or was forced to leave -- her children when she left him for another man). The mother (Isuzu Yamada) has long been away from Tokyo, having moved to Manchuria with her new husband and then being trapped there for years after Japan's surrender. During her imprisonment, her second husband died. Now, she has finally returned to Tokyo with her third husband, to run a mahjong parlor in a seedy neighborhood (and to covertly try to find out how her children are doing).

Ryu's younger daughter, played by Ineko Arima, is an unhappy individual clearly in serious trouble, with no one to turn to. Into this volatile situation, Ozu throws a match -- the return of Ryu's divorced wife (who abandoned -- or was forced to leave -- her children when she left him for another man). The mother (Isuzu Yamada) has long been away from Tokyo, having moved to Manchuria with her new husband and then being trapped there for years after Japan's surrender. During her imprisonment, her second husband died. Now, she has finally returned to Tokyo with her third husband, to run a mahjong parlor in a seedy neighborhood (and to covertly try to find out how her children are doing).

Arima is, literally and figuratively, "in trouble" -- but she trusts neither her father nor her older sister (who clearly had to serve as an inadequate mother substitute -- after the mother's departure when the girl was only three years old). While desperately searching for her boy friend (who is a college student, now studiously avoiding her), she encounters her mother but does not recognize her (all photographs of the mother having been destroyed sixteen years previously). As the young woman spirals further and further down the drain, her mother (who sees her obvious distress) is powerless to help. Not only is she a stranger to the girl, but Hara has demanded that she not reveal her relationship (because it might embarrass Ryu).

Arima is, literally and figuratively, "in trouble" -- but she trusts neither her father nor her older sister (who clearly had to serve as an inadequate mother substitute -- after the mother's departure when the girl was only three years old). While desperately searching for her boy friend (who is a college student, now studiously avoiding her), she encounters her mother but does not recognize her (all photographs of the mother having been destroyed sixteen years previously). As the young woman spirals further and further down the drain, her mother (who sees her obvious distress) is powerless to help. Not only is she a stranger to the girl, but Hara has demanded that she not reveal her relationship (because it might embarrass Ryu).  Meanwhile, neither Ryu nor Hara seems to notice just how unhappy and disturbed Arima actually is. While Ryu seems to like Hara (and his grandchild) well enough (despite being a bit nonplussed by their presence in his household), he never displays the slightest trace of affection for Arima. Ryu attributes Arima's mood and behavior to the fact that she was always a troublesome child.

Meanwhile, neither Ryu nor Hara seems to notice just how unhappy and disturbed Arima actually is. While Ryu seems to like Hara (and his grandchild) well enough (despite being a bit nonplussed by their presence in his household), he never displays the slightest trace of affection for Arima. Ryu attributes Arima's mood and behavior to the fact that she was always a troublesome child.

Some writers (for instance, Joan Mellen) have attacked Tokyo Twilight as being a particularly wrong-headed celebration of the virtues of traditional patriarchal values. Such a reading seems to show utter blindness to what Ozu actually does in this film. Ryu is presented as utterly unfit to deal with the responsibilities of fatherhood (and one suspects he was equally inadequate as a husband). Even in a work context, he is presented as vaguely ridiculous. On the other hand, for all the mother's faults, she is presented sympathetically. Similarly, the dutiful daughter, always attentive to her father's wishes (Hara) often comes across as shrill and unsympathetic, while one's heart is wrung by travails of the unfilial daughter (Arima).

Such a reading seems to show utter blindness to what Ozu actually does in this film. Ryu is presented as utterly unfit to deal with the responsibilities of fatherhood (and one suspects he was equally inadequate as a husband). Even in a work context, he is presented as vaguely ridiculous. On the other hand, for all the mother's faults, she is presented sympathetically. Similarly, the dutiful daughter, always attentive to her father's wishes (Hara) often comes across as shrill and unsympathetic, while one's heart is wrung by travails of the unfilial daughter (Arima).

The fact that Ozu was critiquing (rather than applauding) Japanese patriarchalism here is reinforced by the fact that, after the universal rejection of this somber film, he immediately made another film showing the harm that clueless fathers (exercising patriarchal prerogatives) can cause their daughters -- the delightful, light-hearted Equinox Flower, which showed harm averted by concerted female opposition to paternal authority. Moreover, most of Ozu's subsequent films also involved variations of the very same theme -- but now with sufficient humor to overcome resistance to any subversive message.

The fact that Ozu was critiquing (rather than applauding) Japanese patriarchalism here is reinforced by the fact that, after the universal rejection of this somber film, he immediately made another film showing the harm that clueless fathers (exercising patriarchal prerogatives) can cause their daughters -- the delightful, light-hearted Equinox Flower, which showed harm averted by concerted female opposition to paternal authority. Moreover, most of Ozu's subsequent films also involved variations of the very same theme -- but now with sufficient humor to overcome resistance to any subversive message.

The availability of Tokyo Twilight on English-subtitled DVD (thanks to Criterion's budget-priced Eclipse series) at long last, should markedly increase film lover's familiarity with this important movie. Whether this prickly and difficult film attracts universal approbation or not, it should nonetheless serve to make people more aware of the fact that Ozu was a complicated film maker, whose works covered more diverse territory than genial (or transcendent) acceptance of the status quo.

The availability of Tokyo Twilight on English-subtitled DVD (thanks to Criterion's budget-priced Eclipse series) at long last, should markedly increase film lover's familiarity with this important movie. Whether this prickly and difficult film attracts universal approbation or not, it should nonetheless serve to make people more aware of the fact that Ozu was a complicated film maker, whose works covered more diverse territory than genial (or transcendent) acceptance of the status quo.

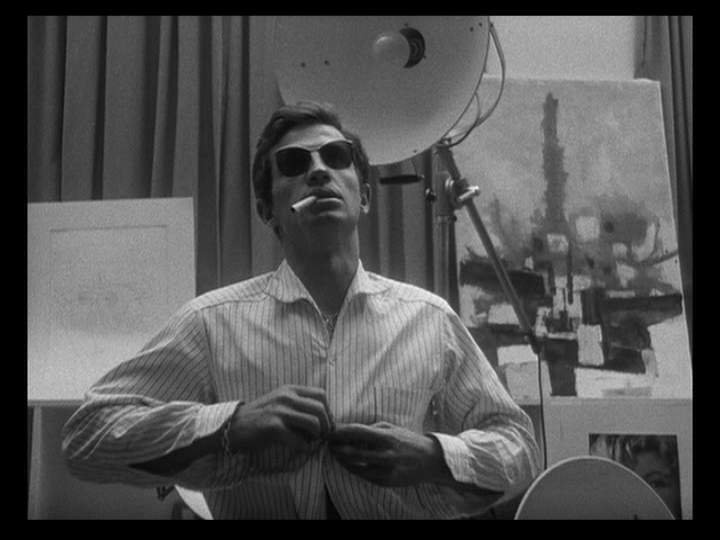

À bout de souffle / Breathless (Jean-Luc Godard, 1960)

As was the case with Potemkin above, this film is too well known (and too much written about) for a "review" to make any sense. Unlike Potemkin, the new DVD of this (from Criterion) did not constitute a re-introduction of an old friend, but rather a first meeting.

As was the case with Potemkin above, this film is too well known (and too much written about) for a "review" to make any sense. Unlike Potemkin, the new DVD of this (from Criterion) did not constitute a re-introduction of an old friend, but rather a first meeting.  Somehow, I had managed not to see this previously -- and reports of the inadequacy of prior DVD versions made me decide to wait until Criterion (seemingly) inevitably tackled its version. I'm glad I waited -- as the new DVD looks very good (and has more extras than I've managed to work my way through to date).

Somehow, I had managed not to see this previously -- and reports of the inadequacy of prior DVD versions made me decide to wait until Criterion (seemingly) inevitably tackled its version. I'm glad I waited -- as the new DVD looks very good (and has more extras than I've managed to work my way through to date).

What can I say about the film? Belmondo is cute and sexy -- even if his is character is often a jerk. Seberg is cute and sexy -- even if her character is a bit of a klutz and a bit of a sneak. The story is interesting -- even if it is often not especially believable. And the images Godard (and cinematographer Raoul Coutard) offer are wonderful. What more does one need?

What can I say about the film? Belmondo is cute and sexy -- even if his is character is often a jerk. Seberg is cute and sexy -- even if her character is a bit of a klutz and a bit of a sneak. The story is interesting -- even if it is often not especially believable. And the images Godard (and cinematographer Raoul Coutard) offer are wonderful. What more does one need?

More pictures:

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/godard/souffle/breath01.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/godard/souffle/breath02.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/godard/souffle/breath03.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/godard/souffle/breath04.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/godard/souffle/breath07.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/godard/souffle/breath08.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/godard/souffle/breath09.png

I first saw this film around 35 years ago -- at a college screening. This screening is also notable for being the only time I stood up and told a bunch of obnoxious noisemakers to shut up and let the rest of the audience experience the film without the "benefit" of their running commentary.

I first saw this film around 35 years ago -- at a college screening. This screening is also notable for being the only time I stood up and told a bunch of obnoxious noisemakers to shut up and let the rest of the audience experience the film without the "benefit" of their running commentary.  At this remote date, I can't recall what musical score this print used -- but I would assume that it was the 1950s version by Nikolai Kryukov. Subsequent viewings (on video and DVD) all utilized a score cobbled together by bits and pieces of Shostakovich works.

At this remote date, I can't recall what musical score this print used -- but I would assume that it was the 1950s version by Nikolai Kryukov. Subsequent viewings (on video and DVD) all utilized a score cobbled together by bits and pieces of Shostakovich works.  Now, at last, there is a restored version that uses the first music composed for the film -- by Edmund Meisel. Although a big fan of Shostakovich in general, I never felt the music borrowed from him fit the film as well as it should. So my main interest in the new DVD (from Kino) was the score.

Now, at last, there is a restored version that uses the first music composed for the film -- by Edmund Meisel. Although a big fan of Shostakovich in general, I never felt the music borrowed from him fit the film as well as it should. So my main interest in the new DVD (from Kino) was the score. As it turns out, Meisel's score (which makes lots of use of the melodies of revolutionary songs from the period in which the film was set) was very effective. But, though I had always been

As it turns out, Meisel's score (which makes lots of use of the melodies of revolutionary songs from the period in which the film was set) was very effective. But, though I had always been  (reasonably) satisfied by the visual quality of my prior DVD, I found the improvement in the image quality in this new release equally striking. For all practical purposes, I find it hard to imagine that this new DVD is likely to be bettered anytime in the foreseeable future.

(reasonably) satisfied by the visual quality of my prior DVD, I found the improvement in the image quality in this new release equally striking. For all practical purposes, I find it hard to imagine that this new DVD is likely to be bettered anytime in the foreseeable future.Arigato-san / Mr. Thank You (Hiroshi Shimizu, 1936)

Alas, no one has ever bothered (yet) to do any DVD release (even unsubtitled) of Shimizu's remarkable chronicle of an ordinary rural bus ride. Filmed almost entirely in (and around) a small bus, as it actually traveled rural roads, this film uncannily anticipates the much later work of directors (like Kiarostami). The film is aggressively limited to the present -- we not only see nothing of the past, we hear virtually nothing about it in the conversations that take place.

Alas, no one has ever bothered (yet) to do any DVD release (even unsubtitled) of Shimizu's remarkable chronicle of an ordinary rural bus ride. Filmed almost entirely in (and around) a small bus, as it actually traveled rural roads, this film uncannily anticipates the much later work of directors (like Kiarostami). The film is aggressively limited to the present -- we not only see nothing of the past, we hear virtually nothing about it in the conversations that take place. The primary cast of character here consists of a good-natured (and good-looking) young bus drive (Ken Uehara), a despondent teenager (Mayumi Tsukiji) and her mother, a fusty old businessman and another young woman (Michiko Kuwano), more sophisticated than the first, but probably not a great deal older.

The primary cast of character here consists of a good-natured (and good-looking) young bus drive (Ken Uehara), a despondent teenager (Mayumi Tsukiji) and her mother, a fusty old businessman and another young woman (Michiko Kuwano), more sophisticated than the first, but probably not a great deal older.  Uehara is called Arigato-san because of his unfailing courtesy as he drives his route -- and he seems to know almost everyone he encounters along the way. Kuwano, dressed in the latest fashions, is clearly interested in Uehara --

Uehara is called Arigato-san because of his unfailing courtesy as he drives his route -- and he seems to know almost everyone he encounters along the way. Kuwano, dressed in the latest fashions, is clearly interested in Uehara --  but he seems to be more intrigued by the sad (kimono-clad) young woman sitting in the back. As it turns out, she is on her way to Tokyo for the purpose of being (for all practical purposes) sold into sexual slavery, due to the destitution of her family. Her chatty mother seems to be willing to talk about their errand -- but the girl, ashamed, doesn't want the topic discussed. T

but he seems to be more intrigued by the sad (kimono-clad) young woman sitting in the back. As it turns out, she is on her way to Tokyo for the purpose of being (for all practical purposes) sold into sexual slavery, due to the destitution of her family. Her chatty mother seems to be willing to talk about their errand -- but the girl, ashamed, doesn't want the topic discussed. T he businessman's main function seems to be as a target for the modern girl's barbs. Meanwhile the driver maintains his composure and sunny disposition, sometimes stopping to chat with people he encounters (especially when they are young and pretty women -- like a pair of traveling musicians and a Korean migrant worker).

he businessman's main function seems to be as a target for the modern girl's barbs. Meanwhile the driver maintains his composure and sunny disposition, sometimes stopping to chat with people he encounters (especially when they are young and pretty women -- like a pair of traveling musicians and a Korean migrant worker). While the modern girl says almost nothing about her own activities and livelihood, it gradually becomes clear that she may well have been in the same situation as her younger "rival" just a few years earlier. As the journey goes on, her effervescence begins to wane, as the the younger woman slowly (and shyly) begins to take notice of the driver.

While the modern girl says almost nothing about her own activities and livelihood, it gradually becomes clear that she may well have been in the same situation as her younger "rival" just a few years earlier. As the journey goes on, her effervescence begins to wane, as the the younger woman slowly (and shyly) begins to take notice of the driver.  Shimizu shows great sympathy to not only these two main heroines, but also to the Korean girl -- who has served as part of a road repair crew (along with her family and other impoverished Koreans) but now must travel (on foot) to a distant part of Japan for her next project. At least during this era, Shimizu might be unique in his expression of open sympathy (here and elsewhere) for foreigners subject to economic oppression and/or prejudice.

Shimizu shows great sympathy to not only these two main heroines, but also to the Korean girl -- who has served as part of a road repair crew (along with her family and other impoverished Koreans) but now must travel (on foot) to a distant part of Japan for her next project. At least during this era, Shimizu might be unique in his expression of open sympathy (here and elsewhere) for foreigners subject to economic oppression and/or prejudice. Apparently there is a nice looking subtitled print of this film, but my exposure has been limited to (first) a very bad looking copy of a television broadcast and (now) a much better (but still not quite satisfactory) copy of a more recent Japanese broadcast. Assuming one is able to enjoy "plotless" Asian films, this film should be considered a "don't miss" if it is shown anywhere reachable -- or eventually becomes available on DVD.

Apparently there is a nice looking subtitled print of this film, but my exposure has been limited to (first) a very bad looking copy of a television broadcast and (now) a much better (but still not quite satisfactory) copy of a more recent Japanese broadcast. Assuming one is able to enjoy "plotless" Asian films, this film should be considered a "don't miss" if it is shown anywhere reachable -- or eventually becomes available on DVD.Tôkyô boshoku / Tokyo Twilight (Yasujiro Ozu, 1957)

When I first watched Tokyo Twilight back in 2001 (courtesy of a now long out of print French video), the film was routinely written off in the English-speaking world as failure -- consistent with the almost uniform rejection of the film by both Japanese critics and audiences at the time of its initial release. While Ozu normally shrugged off problems of this sort (fortunately rare), he apparently was greatly distressed by the poor reception this film received (according to Masahiro Shinoda, then an assistant director working with Ozu).

When I first watched Tokyo Twilight back in 2001 (courtesy of a now long out of print French video), the film was routinely written off in the English-speaking world as failure -- consistent with the almost uniform rejection of the film by both Japanese critics and audiences at the time of its initial release. While Ozu normally shrugged off problems of this sort (fortunately rare), he apparently was greatly distressed by the poor reception this film received (according to Masahiro Shinoda, then an assistant director working with Ozu).  The fact that he had been cautioned in advance by his co-writer Kogo Noda, did not lessen his disappointment. Only a few voices, over the years, offered an alternate view. Donald Richie recognized the fact that Ozu had moved (courageously) into remarkably dark territory in this film -- and Japanese scholar Shigehiko Hasumi pointed out both the value of the film and the importance of factoring it into any comprehensive evaluation of Ozu's work.

The fact that he had been cautioned in advance by his co-writer Kogo Noda, did not lessen his disappointment. Only a few voices, over the years, offered an alternate view. Donald Richie recognized the fact that Ozu had moved (courageously) into remarkably dark territory in this film -- and Japanese scholar Shigehiko Hasumi pointed out both the value of the film and the importance of factoring it into any comprehensive evaluation of Ozu's work.  Unfortunately, Hasumi's comments of Tokyo Twilight never made it into English (while the chapter in his Ozu book that discussed this film was published in translation, virtually all discussion of it was omitted). Only with the widely-traveled 2003 Ozu retrospective (in honor of his hundredth birthday), has there been a critical reappraisal of this long neglected film -- and the dawning of an awareness (almost 50 years after its premiere) that this "flop" might actually be a masterpiece.

Unfortunately, Hasumi's comments of Tokyo Twilight never made it into English (while the chapter in his Ozu book that discussed this film was published in translation, virtually all discussion of it was omitted). Only with the widely-traveled 2003 Ozu retrospective (in honor of his hundredth birthday), has there been a critical reappraisal of this long neglected film -- and the dawning of an awareness (almost 50 years after its premiere) that this "flop" might actually be a masterpiece. Why, one wonders, was the initial reaction to this film so hostile? The answer is probably not too hard to discern. First of all, Ozu dared to have his most universally beloved performers, Chishu Ryu and Setsuko Hara, play roles that were like dark inversions of their normal characters -- not "evil" characters, but deeply flawed ones who ultimately cause a great deal of harm. The single father Ryu plays here is oblivious and inept. Hara plays his eldest daughter, who he previously pushed into a fairly disastrous marriage, and who has just moved back home (with her young child), finding life with her abusive husband intolerable.

Why, one wonders, was the initial reaction to this film so hostile? The answer is probably not too hard to discern. First of all, Ozu dared to have his most universally beloved performers, Chishu Ryu and Setsuko Hara, play roles that were like dark inversions of their normal characters -- not "evil" characters, but deeply flawed ones who ultimately cause a great deal of harm. The single father Ryu plays here is oblivious and inept. Hara plays his eldest daughter, who he previously pushed into a fairly disastrous marriage, and who has just moved back home (with her young child), finding life with her abusive husband intolerable.  Ryu's younger daughter, played by Ineko Arima, is an unhappy individual clearly in serious trouble, with no one to turn to. Into this volatile situation, Ozu throws a match -- the return of Ryu's divorced wife (who abandoned -- or was forced to leave -- her children when she left him for another man). The mother (Isuzu Yamada) has long been away from Tokyo, having moved to Manchuria with her new husband and then being trapped there for years after Japan's surrender. During her imprisonment, her second husband died. Now, she has finally returned to Tokyo with her third husband, to run a mahjong parlor in a seedy neighborhood (and to covertly try to find out how her children are doing).

Ryu's younger daughter, played by Ineko Arima, is an unhappy individual clearly in serious trouble, with no one to turn to. Into this volatile situation, Ozu throws a match -- the return of Ryu's divorced wife (who abandoned -- or was forced to leave -- her children when she left him for another man). The mother (Isuzu Yamada) has long been away from Tokyo, having moved to Manchuria with her new husband and then being trapped there for years after Japan's surrender. During her imprisonment, her second husband died. Now, she has finally returned to Tokyo with her third husband, to run a mahjong parlor in a seedy neighborhood (and to covertly try to find out how her children are doing). Arima is, literally and figuratively, "in trouble" -- but she trusts neither her father nor her older sister (who clearly had to serve as an inadequate mother substitute -- after the mother's departure when the girl was only three years old). While desperately searching for her boy friend (who is a college student, now studiously avoiding her), she encounters her mother but does not recognize her (all photographs of the mother having been destroyed sixteen years previously). As the young woman spirals further and further down the drain, her mother (who sees her obvious distress) is powerless to help. Not only is she a stranger to the girl, but Hara has demanded that she not reveal her relationship (because it might embarrass Ryu).

Arima is, literally and figuratively, "in trouble" -- but she trusts neither her father nor her older sister (who clearly had to serve as an inadequate mother substitute -- after the mother's departure when the girl was only three years old). While desperately searching for her boy friend (who is a college student, now studiously avoiding her), she encounters her mother but does not recognize her (all photographs of the mother having been destroyed sixteen years previously). As the young woman spirals further and further down the drain, her mother (who sees her obvious distress) is powerless to help. Not only is she a stranger to the girl, but Hara has demanded that she not reveal her relationship (because it might embarrass Ryu).  Meanwhile, neither Ryu nor Hara seems to notice just how unhappy and disturbed Arima actually is. While Ryu seems to like Hara (and his grandchild) well enough (despite being a bit nonplussed by their presence in his household), he never displays the slightest trace of affection for Arima. Ryu attributes Arima's mood and behavior to the fact that she was always a troublesome child.

Meanwhile, neither Ryu nor Hara seems to notice just how unhappy and disturbed Arima actually is. While Ryu seems to like Hara (and his grandchild) well enough (despite being a bit nonplussed by their presence in his household), he never displays the slightest trace of affection for Arima. Ryu attributes Arima's mood and behavior to the fact that she was always a troublesome child.Some writers (for instance, Joan Mellen) have attacked Tokyo Twilight as being a particularly wrong-headed celebration of the virtues of traditional patriarchal values.

Such a reading seems to show utter blindness to what Ozu actually does in this film. Ryu is presented as utterly unfit to deal with the responsibilities of fatherhood (and one suspects he was equally inadequate as a husband). Even in a work context, he is presented as vaguely ridiculous. On the other hand, for all the mother's faults, she is presented sympathetically. Similarly, the dutiful daughter, always attentive to her father's wishes (Hara) often comes across as shrill and unsympathetic, while one's heart is wrung by travails of the unfilial daughter (Arima).

Such a reading seems to show utter blindness to what Ozu actually does in this film. Ryu is presented as utterly unfit to deal with the responsibilities of fatherhood (and one suspects he was equally inadequate as a husband). Even in a work context, he is presented as vaguely ridiculous. On the other hand, for all the mother's faults, she is presented sympathetically. Similarly, the dutiful daughter, always attentive to her father's wishes (Hara) often comes across as shrill and unsympathetic, while one's heart is wrung by travails of the unfilial daughter (Arima). The fact that Ozu was critiquing (rather than applauding) Japanese patriarchalism here is reinforced by the fact that, after the universal rejection of this somber film, he immediately made another film showing the harm that clueless fathers (exercising patriarchal prerogatives) can cause their daughters -- the delightful, light-hearted Equinox Flower, which showed harm averted by concerted female opposition to paternal authority. Moreover, most of Ozu's subsequent films also involved variations of the very same theme -- but now with sufficient humor to overcome resistance to any subversive message.

The fact that Ozu was critiquing (rather than applauding) Japanese patriarchalism here is reinforced by the fact that, after the universal rejection of this somber film, he immediately made another film showing the harm that clueless fathers (exercising patriarchal prerogatives) can cause their daughters -- the delightful, light-hearted Equinox Flower, which showed harm averted by concerted female opposition to paternal authority. Moreover, most of Ozu's subsequent films also involved variations of the very same theme -- but now with sufficient humor to overcome resistance to any subversive message. The availability of Tokyo Twilight on English-subtitled DVD (thanks to Criterion's budget-priced Eclipse series) at long last, should markedly increase film lover's familiarity with this important movie. Whether this prickly and difficult film attracts universal approbation or not, it should nonetheless serve to make people more aware of the fact that Ozu was a complicated film maker, whose works covered more diverse territory than genial (or transcendent) acceptance of the status quo.

The availability of Tokyo Twilight on English-subtitled DVD (thanks to Criterion's budget-priced Eclipse series) at long last, should markedly increase film lover's familiarity with this important movie. Whether this prickly and difficult film attracts universal approbation or not, it should nonetheless serve to make people more aware of the fact that Ozu was a complicated film maker, whose works covered more diverse territory than genial (or transcendent) acceptance of the status quo.À bout de souffle / Breathless (Jean-Luc Godard, 1960)

As was the case with Potemkin above, this film is too well known (and too much written about) for a "review" to make any sense. Unlike Potemkin, the new DVD of this (from Criterion) did not constitute a re-introduction of an old friend, but rather a first meeting.

As was the case with Potemkin above, this film is too well known (and too much written about) for a "review" to make any sense. Unlike Potemkin, the new DVD of this (from Criterion) did not constitute a re-introduction of an old friend, but rather a first meeting.  Somehow, I had managed not to see this previously -- and reports of the inadequacy of prior DVD versions made me decide to wait until Criterion (seemingly) inevitably tackled its version. I'm glad I waited -- as the new DVD looks very good (and has more extras than I've managed to work my way through to date).

Somehow, I had managed not to see this previously -- and reports of the inadequacy of prior DVD versions made me decide to wait until Criterion (seemingly) inevitably tackled its version. I'm glad I waited -- as the new DVD looks very good (and has more extras than I've managed to work my way through to date). What can I say about the film? Belmondo is cute and sexy -- even if his is character is often a jerk. Seberg is cute and sexy -- even if her character is a bit of a klutz and a bit of a sneak. The story is interesting -- even if it is often not especially believable. And the images Godard (and cinematographer Raoul Coutard) offer are wonderful. What more does one need?

What can I say about the film? Belmondo is cute and sexy -- even if his is character is often a jerk. Seberg is cute and sexy -- even if her character is a bit of a klutz and a bit of a sneak. The story is interesting -- even if it is often not especially believable. And the images Godard (and cinematographer Raoul Coutard) offer are wonderful. What more does one need?More pictures:

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/godard/souffle/breath01.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/godard/souffle/breath02.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/godard/souffle/breath03.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/godard/souffle/breath04.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/godard/souffle/breath07.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/godard/souffle/breath08.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/godard/souffle/breath09.png

Comments