Watched December 10-16, 2007 (part one): Kozintsev and Trauberg

Due to the (increasing) tendency of my posts to slip further and further behind my viewing of movies, I've decided to start breaking my weekly posts up into smaller pieces. And I may take more radical action soon, separating the list of what I watch on an an ongoing basis (which I would try to keep as current as possible) from the reviews (which might take longer to appear). In any event, this week's submission comes in two parts. Part two will move from 1930s Russia to early 1950s Japan.

Yunost Maksima / Maxim's Youth (Grigori Kozintsev & Leonid Trauberg, 1935)

The previous film by Kozintsev and Trauberg was Alone, a pre-talkie with a synchronized score by Dmitri Shostakovich, sound effects and even snippets of speech. With this first film of their Maxim trilogy, they entered the realm of talkies. Nonetheless, this film (and its two successors) retained many features from the silent era -- like long wordless sequences and occasional intertitles.

The previous film by Kozintsev and Trauberg was Alone, a pre-talkie with a synchronized score by Dmitri Shostakovich, sound effects and even snippets of speech. With this first film of their Maxim trilogy, they entered the realm of talkies. Nonetheless, this film (and its two successors) retained many features from the silent era -- like long wordless sequences and occasional intertitles.  This film also has a bit of music by Shostakovich, accompanying a silent-esque sequence of rich revelers celebrating New Year's Eve by a rather inebriated sleigh race through the streets of St. Petersburg. Revolutionary songs (sung and/or played on the accordion) make up most of the music for the rest of this film.

This film also has a bit of music by Shostakovich, accompanying a silent-esque sequence of rich revelers celebrating New Year's Eve by a rather inebriated sleigh race through the streets of St. Petersburg. Revolutionary songs (sung and/or played on the accordion) make up most of the music for the rest of this film.

The first film of the trilogy is set in 1910 (once it gets past the last day of 1909). Its protagonist is Maxim (Boris Chirkov), who is sort of a Soviet (initially pre-Soviet) Everyman. He starts out as a rather heedless young worker and progressively becomes entangled in union activity, which is (of course) viewed as subversive by the owners of his factory and the Czarist authorities. He has two male buddies, who are even less political than himself -- and a female acquaintance,

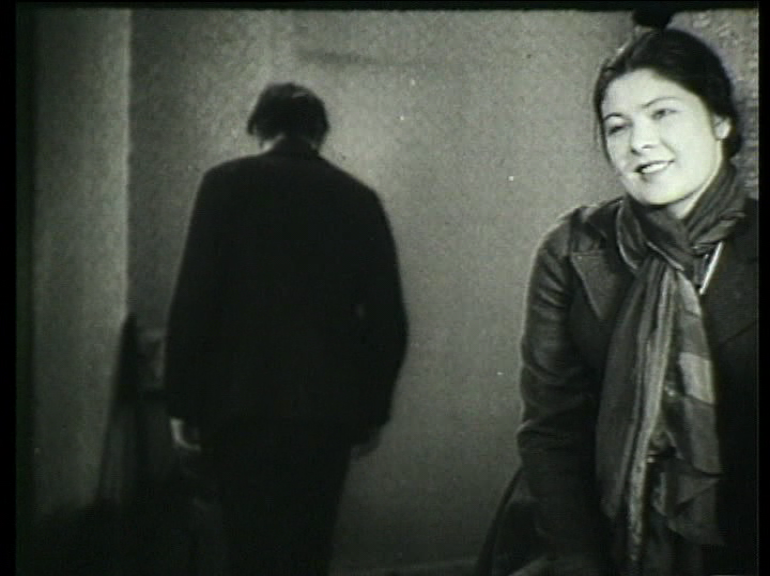

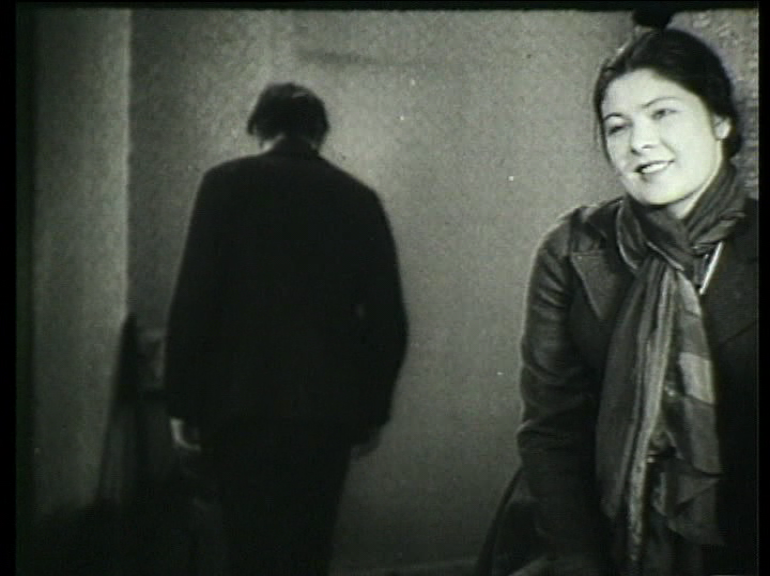

The first film of the trilogy is set in 1910 (once it gets past the last day of 1909). Its protagonist is Maxim (Boris Chirkov), who is sort of a Soviet (initially pre-Soviet) Everyman. He starts out as a rather heedless young worker and progressively becomes entangled in union activity, which is (of course) viewed as subversive by the owners of his factory and the Czarist authorities. He has two male buddies, who are even less political than himself -- and a female acquaintance,  Natasha (Valentina Kibardina), who is up to her neck in labor organization and other left wing political activities, working under the direction of a veteran politician, Polivanov (Mikhail Tarkhanov). Maxim's radicalization begins with the death of one of his comrades due to dangerous conditions at the factory. When the dead man's co-workers hold a funeral procession for him, it is smashed by Army troops.

Natasha (Valentina Kibardina), who is up to her neck in labor organization and other left wing political activities, working under the direction of a veteran politician, Polivanov (Mikhail Tarkhanov). Maxim's radicalization begins with the death of one of his comrades due to dangerous conditions at the factory. When the dead man's co-workers hold a funeral procession for him, it is smashed by Army troops.  This leads to further unrest, into which Maxim and his remaining colleague are swept. Both are arrested, but the friend makes the mistake of violently resisting arrest. In prison, as the condemned prisoners are being led off to be executed, Maxim and his comrades protest by singing the "Internationale", bringing more punishment on their heads.

This leads to further unrest, into which Maxim and his remaining colleague are swept. Both are arrested, but the friend makes the mistake of violently resisting arrest. In prison, as the condemned prisoners are being led off to be executed, Maxim and his comrades protest by singing the "Internationale", bringing more punishment on their heads.

Maxim is eventually exiled to any place in Russia except St. Petersburg and Moscow and about thirty other cities and districts (leaving only rural boondocks open to him). After bidding a last farewell to Natasha (now undercover -- as a member of the upper bourgeoisie), Maxim departs for the countryside. But even there, he manages to get tangled up in labor troubles (strumming his guitar, he gives coded directions on where a secret worker's rally is to be held); this time he escapes capture, but just barely.

(leaving only rural boondocks open to him). After bidding a last farewell to Natasha (now undercover -- as a member of the upper bourgeoisie), Maxim departs for the countryside. But even there, he manages to get tangled up in labor troubles (strumming his guitar, he gives coded directions on where a secret worker's rally is to be held); this time he escapes capture, but just barely.

The style Kozintsev and Trauberg utilize here is closer to the populist one practiced by Boris Barnet than to the more avant-garde work of Eisenstein. But this film shows plenty of traces of the expressionistic style used in their earlier masterpiece New Babylon, particularly in the way lighting is used. The cinematography (by long-time collaborator Andrei Moskvin) is often quite striking, considerably more sophisticated than the relatively simple (albeit interesting) plot.

The style Kozintsev and Trauberg utilize here is closer to the populist one practiced by Boris Barnet than to the more avant-garde work of Eisenstein. But this film shows plenty of traces of the expressionistic style used in their earlier masterpiece New Babylon, particularly in the way lighting is used. The cinematography (by long-time collaborator Andrei Moskvin) is often quite striking, considerably more sophisticated than the relatively simple (albeit interesting) plot.

No English-subtitled DVD is available, but the French-subtitled version from Bach Films is serviceable -- and cheap. More pictures:

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/kozintsev/maxim/youth02.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/kozintsev/maxim/youth06.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/kozintsev/maxim/youth07.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/kozintsev/maxim/youth09.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/kozintsev/maxim/youth11.png

Vozvrashcheniye Maksima / The Return of Maxim (Grigori Kozintsev & Leonid Trauberg, 1937)

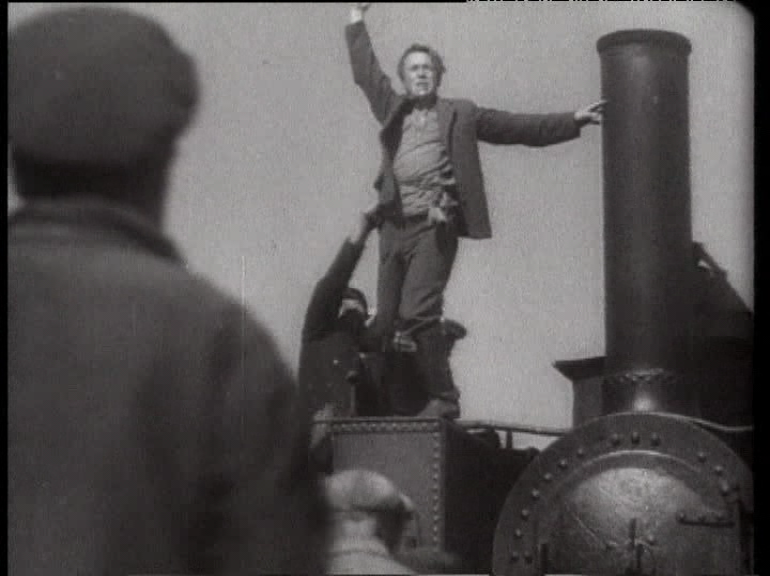

Part two of the trilogy, is set in 1914. It is set in St. Petersburg (soon to be renamed Petrograd) --as Maxim has now returned there (still armed, Woody Guthrie-like, with a guitar). Maxim has now openly joined the ranks of revolutionary agitators,

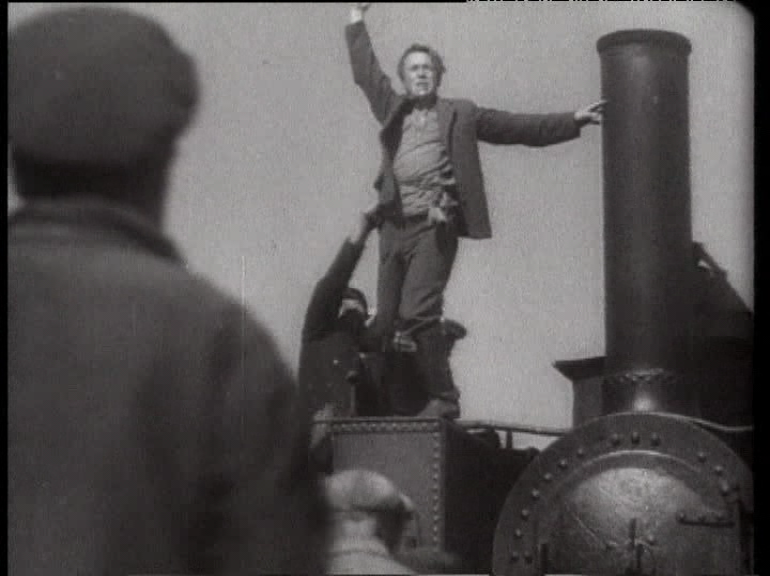

Part two of the trilogy, is set in 1914. It is set in St. Petersburg (soon to be renamed Petrograd) --as Maxim has now returned there (still armed, Woody Guthrie-like, with a guitar). Maxim has now openly joined the ranks of revolutionary agitators,  along with Natasha who sheds her "respectable" alter ego soon after his return (she acted as a spy, while in a rather courtesan-like situation). Labor troubles are now general, as the First World War is having a devastating impact on the lives of ordinary workers. Maxim is waylaid (and almost killed), and then disappears -- leading his comrades to fear the worst.

along with Natasha who sheds her "respectable" alter ego soon after his return (she acted as a spy, while in a rather courtesan-like situation). Labor troubles are now general, as the First World War is having a devastating impact on the lives of ordinary workers. Maxim is waylaid (and almost killed), and then disappears -- leading his comrades to fear the worst.

Recovered, Maxim helps coordinate a general strike. When attempts to suppress a massive march by the strikers are turned back, the strike turns into an insurrection of sorts. At this point, the Tsarist government sends in troops in full force,

Recovered, Maxim helps coordinate a general strike. When attempts to suppress a massive march by the strikers are turned back, the strike turns into an insurrection of sorts. At this point, the Tsarist government sends in troops in full force,  overwhelming the workers' feeble barricades. Some of the comrades are killed, and others (including Natasha) are captured. Maxim escapes -- by joining the army, where he will continue to campaign for political change, on the front lines.

overwhelming the workers' feeble barricades. Some of the comrades are killed, and others (including Natasha) are captured. Maxim escapes -- by joining the army, where he will continue to campaign for political change, on the front lines.

Visually, this is a simpler film than its predecessor. Not that there is no mood and atmosphere (when needed), but the style is more vigorous and direct. The success of the first film obviously made greater resources available to the film makers --

Visually, this is a simpler film than its predecessor. Not that there is no mood and atmosphere (when needed), but the style is more vigorous and direct. The success of the first film obviously made greater resources available to the film makers --  and some of the gigantic crowd scenes are quite impressive. This film. like the first, offers a blend of comedy, romance, suspense, music (with more contributions by Shostakovich) and "propaganda". Overall, Kozintsev and Trauberg seem more concerned with the fate of their characters (and the working poor), than in selling ideology here.

and some of the gigantic crowd scenes are quite impressive. This film. like the first, offers a blend of comedy, romance, suspense, music (with more contributions by Shostakovich) and "propaganda". Overall, Kozintsev and Trauberg seem more concerned with the fate of their characters (and the working poor), than in selling ideology here.

Additonal screen shots:

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/kozintsev/maxim/return01.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/kozintsev/maxim/return03.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/kozintsev/maxim/return06.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/kozintsev/maxim/return07.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/kozintsev/maxim/return10.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/kozintsev/maxim/return12.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/kozintsev/maxim/return13.png

Vyborgskaya storona/ The Vyborg District (Grigori Kozintsev & Leonid Trauberg, 1939)

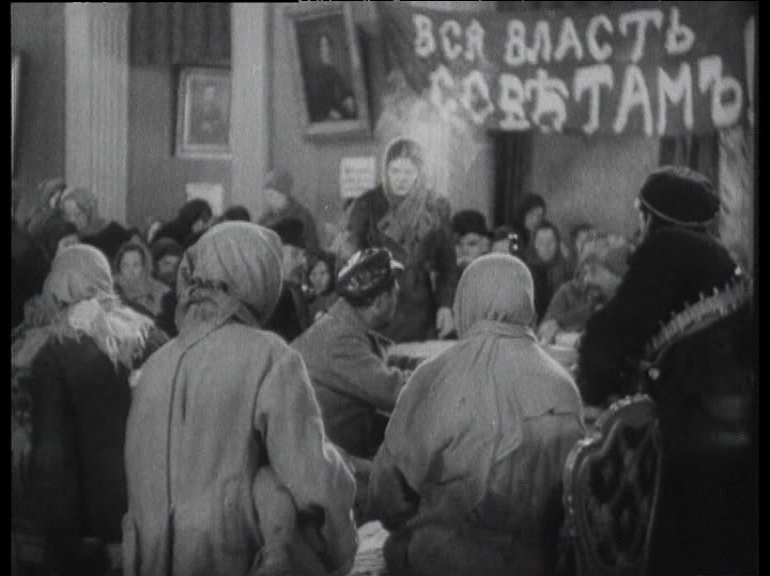

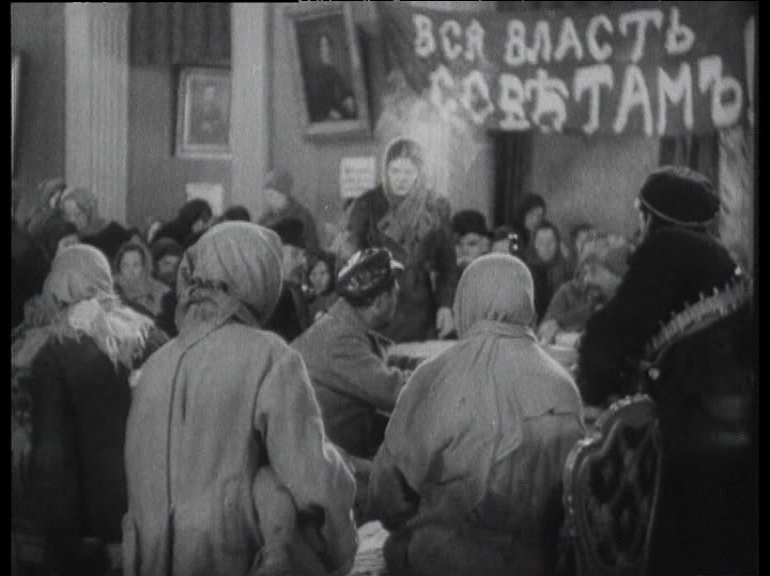

With this film, we move (with Maxim) to 1917, around the time of the October Revolution. Interestingly, we none of the "action" featured in other soviet films set in this period, rather the political focus is on parliamentary wrangling. Meanwhile, Maxim himself has been appointed commissar of a leading bank, and the old management is far from happy (and does its best at obstructing oversight).

With this film, we move (with Maxim) to 1917, around the time of the October Revolution. Interestingly, we none of the "action" featured in other soviet films set in this period, rather the political focus is on parliamentary wrangling. Meanwhile, Maxim himself has been appointed commissar of a leading bank, and the old management is far from happy (and does its best at obstructing oversight).  Counter-revolutionaries, making use of economic chaos, try to stir up unrest among the unemployed poor in order to provide cover for a plot to assassinate Lenin. Natasha is busy representing the local worker's organization in the Vyborgsky District (then one of the city's major industrial areas), making demands for more financial help than the government and banks (viz. Maxim) were able to provide. The climax of the film is the trial of looters, including Yevdokia (Natalya Uzhviy),

Counter-revolutionaries, making use of economic chaos, try to stir up unrest among the unemployed poor in order to provide cover for a plot to assassinate Lenin. Natasha is busy representing the local worker's organization in the Vyborgsky District (then one of the city's major industrial areas), making demands for more financial help than the government and banks (viz. Maxim) were able to provide. The climax of the film is the trial of looters, including Yevdokia (Natalya Uzhviy),  as an impoverished war widow with a sick child, who got ensnared in the unrest due to desperation. Clemency by the people's court, once it hears her circumstances, leads to the capture of one of the leading counter-revolutionaries. At the end of the film, Maxim is once again on his way to fight, this time for the (new) government.

as an impoverished war widow with a sick child, who got ensnared in the unrest due to desperation. Clemency by the people's court, once it hears her circumstances, leads to the capture of one of the leading counter-revolutionaries. At the end of the film, Maxim is once again on his way to fight, this time for the (new) government.

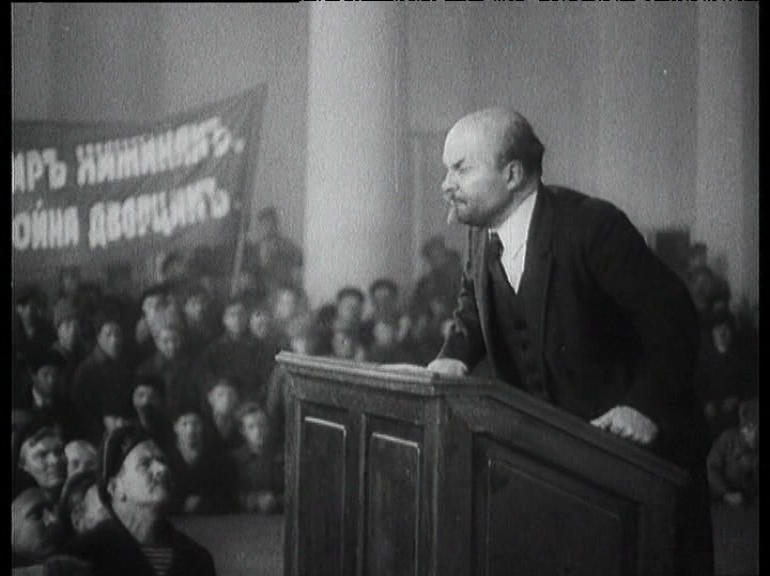

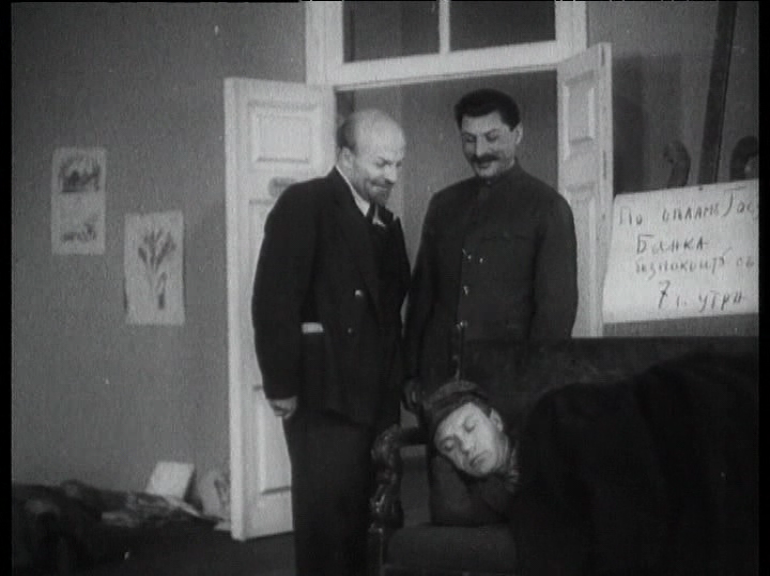

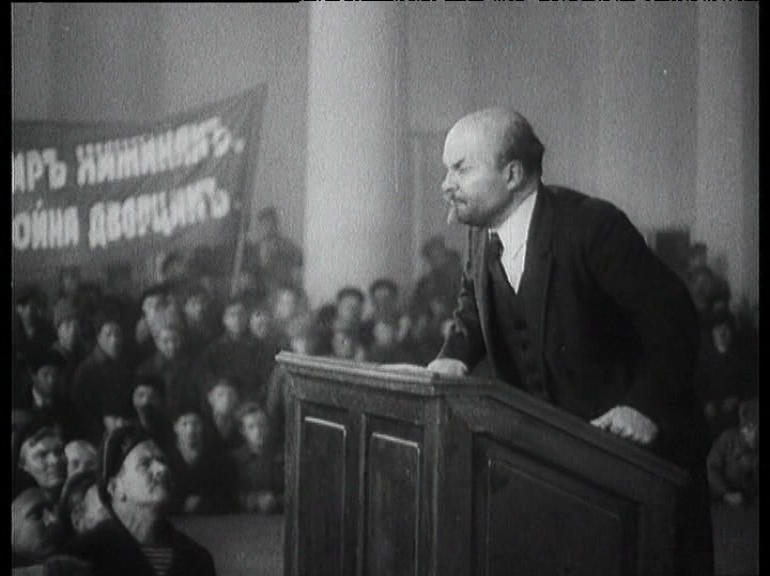

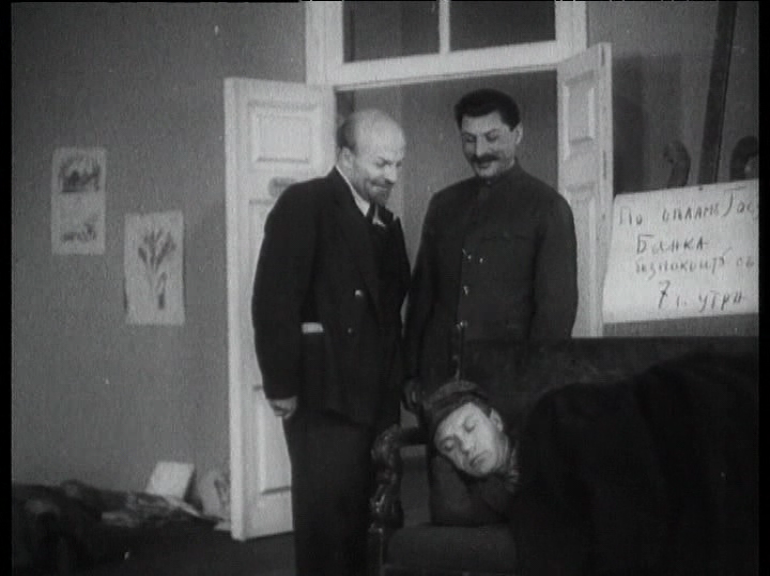

Given the subject matter, this is the most frankly political film of the trilogy -- and it features appearances by Lenin, Trotsky (renamed Sverdlov) and Stalin. While they mainly appear in the "governmental" sections of the film, they do interact with Maxim on occasion. Most amusingly, when they find Maxim taking a catnap, after staying up all night to work,

Given the subject matter, this is the most frankly political film of the trilogy -- and it features appearances by Lenin, Trotsky (renamed Sverdlov) and Stalin. While they mainly appear in the "governmental" sections of the film, they do interact with Maxim on occasion. Most amusingly, when they find Maxim taking a catnap, after staying up all night to work,  Lenin has Stalin add another hour to the time that Maxim had designated for wakening by his colleagues. The handling of political issues is more heavy-handed here, by necessity. Still, Kozintsev and Trauberg generally keep one interested in the proceedings. As with the preceding film, this features less in the way of stylistic flourishes than did Maxim's Youth -- and the cinematography (still by Moskvin) suits the direct style.

Lenin has Stalin add another hour to the time that Maxim had designated for wakening by his colleagues. The handling of political issues is more heavy-handed here, by necessity. Still, Kozintsev and Trauberg generally keep one interested in the proceedings. As with the preceding film, this features less in the way of stylistic flourishes than did Maxim's Youth -- and the cinematography (still by Moskvin) suits the direct style.

Needless to say, the film also features more music by Shostakovich. To tel the truth, one of the main reasons I ordered the Maxim trilogy from Bach Films was to see and hear how Shostakovich's music was used in context. Disembodied scores can be musically effective --

Needless to say, the film also features more music by Shostakovich. To tel the truth, one of the main reasons I ordered the Maxim trilogy from Bach Films was to see and hear how Shostakovich's music was used in context. Disembodied scores can be musically effective --  but (for scores I like) I really feel the need to find out how the musically is actually used. The fact that the films were visually pleasing and generally interesting and entertaining was a nice bonus. While the Maxim films are not as remarkable as Kozintsev's and Trauberg's masterpieces, New Babylon and Alone, they are nonetheless of more than simply historical interest.

but (for scores I like) I really feel the need to find out how the musically is actually used. The fact that the films were visually pleasing and generally interesting and entertaining was a nice bonus. While the Maxim films are not as remarkable as Kozintsev's and Trauberg's masterpieces, New Babylon and Alone, they are nonetheless of more than simply historical interest.

More screen captures:

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/kozintsev/maxim/vyborg04.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/kozintsev/maxim/vyborg05.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/kozintsev/maxim/vyborg07.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/kozintsev/maxim/vyborg09.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/kozintsev/maxim/vyborg11.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/kozintsev/maxim/vyborg12.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/kozintsev/maxim/vyborg14.png

Yunost Maksima / Maxim's Youth (Grigori Kozintsev & Leonid Trauberg, 1935)

The previous film by Kozintsev and Trauberg was Alone, a pre-talkie with a synchronized score by Dmitri Shostakovich, sound effects and even snippets of speech. With this first film of their Maxim trilogy, they entered the realm of talkies. Nonetheless, this film (and its two successors) retained many features from the silent era -- like long wordless sequences and occasional intertitles.

The previous film by Kozintsev and Trauberg was Alone, a pre-talkie with a synchronized score by Dmitri Shostakovich, sound effects and even snippets of speech. With this first film of their Maxim trilogy, they entered the realm of talkies. Nonetheless, this film (and its two successors) retained many features from the silent era -- like long wordless sequences and occasional intertitles.  This film also has a bit of music by Shostakovich, accompanying a silent-esque sequence of rich revelers celebrating New Year's Eve by a rather inebriated sleigh race through the streets of St. Petersburg. Revolutionary songs (sung and/or played on the accordion) make up most of the music for the rest of this film.

This film also has a bit of music by Shostakovich, accompanying a silent-esque sequence of rich revelers celebrating New Year's Eve by a rather inebriated sleigh race through the streets of St. Petersburg. Revolutionary songs (sung and/or played on the accordion) make up most of the music for the rest of this film. The first film of the trilogy is set in 1910 (once it gets past the last day of 1909). Its protagonist is Maxim (Boris Chirkov), who is sort of a Soviet (initially pre-Soviet) Everyman. He starts out as a rather heedless young worker and progressively becomes entangled in union activity, which is (of course) viewed as subversive by the owners of his factory and the Czarist authorities. He has two male buddies, who are even less political than himself -- and a female acquaintance,

The first film of the trilogy is set in 1910 (once it gets past the last day of 1909). Its protagonist is Maxim (Boris Chirkov), who is sort of a Soviet (initially pre-Soviet) Everyman. He starts out as a rather heedless young worker and progressively becomes entangled in union activity, which is (of course) viewed as subversive by the owners of his factory and the Czarist authorities. He has two male buddies, who are even less political than himself -- and a female acquaintance,  Natasha (Valentina Kibardina), who is up to her neck in labor organization and other left wing political activities, working under the direction of a veteran politician, Polivanov (Mikhail Tarkhanov). Maxim's radicalization begins with the death of one of his comrades due to dangerous conditions at the factory. When the dead man's co-workers hold a funeral procession for him, it is smashed by Army troops.

Natasha (Valentina Kibardina), who is up to her neck in labor organization and other left wing political activities, working under the direction of a veteran politician, Polivanov (Mikhail Tarkhanov). Maxim's radicalization begins with the death of one of his comrades due to dangerous conditions at the factory. When the dead man's co-workers hold a funeral procession for him, it is smashed by Army troops.  This leads to further unrest, into which Maxim and his remaining colleague are swept. Both are arrested, but the friend makes the mistake of violently resisting arrest. In prison, as the condemned prisoners are being led off to be executed, Maxim and his comrades protest by singing the "Internationale", bringing more punishment on their heads.

This leads to further unrest, into which Maxim and his remaining colleague are swept. Both are arrested, but the friend makes the mistake of violently resisting arrest. In prison, as the condemned prisoners are being led off to be executed, Maxim and his comrades protest by singing the "Internationale", bringing more punishment on their heads.Maxim is eventually exiled to any place in Russia except St. Petersburg and Moscow and about thirty other cities and districts

(leaving only rural boondocks open to him). After bidding a last farewell to Natasha (now undercover -- as a member of the upper bourgeoisie), Maxim departs for the countryside. But even there, he manages to get tangled up in labor troubles (strumming his guitar, he gives coded directions on where a secret worker's rally is to be held); this time he escapes capture, but just barely.

(leaving only rural boondocks open to him). After bidding a last farewell to Natasha (now undercover -- as a member of the upper bourgeoisie), Maxim departs for the countryside. But even there, he manages to get tangled up in labor troubles (strumming his guitar, he gives coded directions on where a secret worker's rally is to be held); this time he escapes capture, but just barely. The style Kozintsev and Trauberg utilize here is closer to the populist one practiced by Boris Barnet than to the more avant-garde work of Eisenstein. But this film shows plenty of traces of the expressionistic style used in their earlier masterpiece New Babylon, particularly in the way lighting is used. The cinematography (by long-time collaborator Andrei Moskvin) is often quite striking, considerably more sophisticated than the relatively simple (albeit interesting) plot.

The style Kozintsev and Trauberg utilize here is closer to the populist one practiced by Boris Barnet than to the more avant-garde work of Eisenstein. But this film shows plenty of traces of the expressionistic style used in their earlier masterpiece New Babylon, particularly in the way lighting is used. The cinematography (by long-time collaborator Andrei Moskvin) is often quite striking, considerably more sophisticated than the relatively simple (albeit interesting) plot.No English-subtitled DVD is available, but the French-subtitled version from Bach Films is serviceable -- and cheap. More pictures:

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/kozintsev/maxim/youth02.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/kozintsev/maxim/youth06.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/kozintsev/maxim/youth07.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/kozintsev/maxim/youth09.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/kozintsev/maxim/youth11.png

Vozvrashcheniye Maksima / The Return of Maxim (Grigori Kozintsev & Leonid Trauberg, 1937)

Part two of the trilogy, is set in 1914. It is set in St. Petersburg (soon to be renamed Petrograd) --as Maxim has now returned there (still armed, Woody Guthrie-like, with a guitar). Maxim has now openly joined the ranks of revolutionary agitators,

Part two of the trilogy, is set in 1914. It is set in St. Petersburg (soon to be renamed Petrograd) --as Maxim has now returned there (still armed, Woody Guthrie-like, with a guitar). Maxim has now openly joined the ranks of revolutionary agitators,  along with Natasha who sheds her "respectable" alter ego soon after his return (she acted as a spy, while in a rather courtesan-like situation). Labor troubles are now general, as the First World War is having a devastating impact on the lives of ordinary workers. Maxim is waylaid (and almost killed), and then disappears -- leading his comrades to fear the worst.

along with Natasha who sheds her "respectable" alter ego soon after his return (she acted as a spy, while in a rather courtesan-like situation). Labor troubles are now general, as the First World War is having a devastating impact on the lives of ordinary workers. Maxim is waylaid (and almost killed), and then disappears -- leading his comrades to fear the worst. Recovered, Maxim helps coordinate a general strike. When attempts to suppress a massive march by the strikers are turned back, the strike turns into an insurrection of sorts. At this point, the Tsarist government sends in troops in full force,

Recovered, Maxim helps coordinate a general strike. When attempts to suppress a massive march by the strikers are turned back, the strike turns into an insurrection of sorts. At this point, the Tsarist government sends in troops in full force,  overwhelming the workers' feeble barricades. Some of the comrades are killed, and others (including Natasha) are captured. Maxim escapes -- by joining the army, where he will continue to campaign for political change, on the front lines.

overwhelming the workers' feeble barricades. Some of the comrades are killed, and others (including Natasha) are captured. Maxim escapes -- by joining the army, where he will continue to campaign for political change, on the front lines. Visually, this is a simpler film than its predecessor. Not that there is no mood and atmosphere (when needed), but the style is more vigorous and direct. The success of the first film obviously made greater resources available to the film makers --

Visually, this is a simpler film than its predecessor. Not that there is no mood and atmosphere (when needed), but the style is more vigorous and direct. The success of the first film obviously made greater resources available to the film makers --  and some of the gigantic crowd scenes are quite impressive. This film. like the first, offers a blend of comedy, romance, suspense, music (with more contributions by Shostakovich) and "propaganda". Overall, Kozintsev and Trauberg seem more concerned with the fate of their characters (and the working poor), than in selling ideology here.

and some of the gigantic crowd scenes are quite impressive. This film. like the first, offers a blend of comedy, romance, suspense, music (with more contributions by Shostakovich) and "propaganda". Overall, Kozintsev and Trauberg seem more concerned with the fate of their characters (and the working poor), than in selling ideology here.Additonal screen shots:

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/kozintsev/maxim/return01.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/kozintsev/maxim/return03.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/kozintsev/maxim/return06.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/kozintsev/maxim/return07.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/kozintsev/maxim/return10.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/kozintsev/maxim/return12.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/kozintsev/maxim/return13.png

Vyborgskaya storona/ The Vyborg District (Grigori Kozintsev & Leonid Trauberg, 1939)

With this film, we move (with Maxim) to 1917, around the time of the October Revolution. Interestingly, we none of the "action" featured in other soviet films set in this period, rather the political focus is on parliamentary wrangling. Meanwhile, Maxim himself has been appointed commissar of a leading bank, and the old management is far from happy (and does its best at obstructing oversight).

With this film, we move (with Maxim) to 1917, around the time of the October Revolution. Interestingly, we none of the "action" featured in other soviet films set in this period, rather the political focus is on parliamentary wrangling. Meanwhile, Maxim himself has been appointed commissar of a leading bank, and the old management is far from happy (and does its best at obstructing oversight).  Counter-revolutionaries, making use of economic chaos, try to stir up unrest among the unemployed poor in order to provide cover for a plot to assassinate Lenin. Natasha is busy representing the local worker's organization in the Vyborgsky District (then one of the city's major industrial areas), making demands for more financial help than the government and banks (viz. Maxim) were able to provide. The climax of the film is the trial of looters, including Yevdokia (Natalya Uzhviy),

Counter-revolutionaries, making use of economic chaos, try to stir up unrest among the unemployed poor in order to provide cover for a plot to assassinate Lenin. Natasha is busy representing the local worker's organization in the Vyborgsky District (then one of the city's major industrial areas), making demands for more financial help than the government and banks (viz. Maxim) were able to provide. The climax of the film is the trial of looters, including Yevdokia (Natalya Uzhviy),  as an impoverished war widow with a sick child, who got ensnared in the unrest due to desperation. Clemency by the people's court, once it hears her circumstances, leads to the capture of one of the leading counter-revolutionaries. At the end of the film, Maxim is once again on his way to fight, this time for the (new) government.

as an impoverished war widow with a sick child, who got ensnared in the unrest due to desperation. Clemency by the people's court, once it hears her circumstances, leads to the capture of one of the leading counter-revolutionaries. At the end of the film, Maxim is once again on his way to fight, this time for the (new) government. Given the subject matter, this is the most frankly political film of the trilogy -- and it features appearances by Lenin, Trotsky (renamed Sverdlov) and Stalin. While they mainly appear in the "governmental" sections of the film, they do interact with Maxim on occasion. Most amusingly, when they find Maxim taking a catnap, after staying up all night to work,

Given the subject matter, this is the most frankly political film of the trilogy -- and it features appearances by Lenin, Trotsky (renamed Sverdlov) and Stalin. While they mainly appear in the "governmental" sections of the film, they do interact with Maxim on occasion. Most amusingly, when they find Maxim taking a catnap, after staying up all night to work,  Lenin has Stalin add another hour to the time that Maxim had designated for wakening by his colleagues. The handling of political issues is more heavy-handed here, by necessity. Still, Kozintsev and Trauberg generally keep one interested in the proceedings. As with the preceding film, this features less in the way of stylistic flourishes than did Maxim's Youth -- and the cinematography (still by Moskvin) suits the direct style.

Lenin has Stalin add another hour to the time that Maxim had designated for wakening by his colleagues. The handling of political issues is more heavy-handed here, by necessity. Still, Kozintsev and Trauberg generally keep one interested in the proceedings. As with the preceding film, this features less in the way of stylistic flourishes than did Maxim's Youth -- and the cinematography (still by Moskvin) suits the direct style. Needless to say, the film also features more music by Shostakovich. To tel the truth, one of the main reasons I ordered the Maxim trilogy from Bach Films was to see and hear how Shostakovich's music was used in context. Disembodied scores can be musically effective --

Needless to say, the film also features more music by Shostakovich. To tel the truth, one of the main reasons I ordered the Maxim trilogy from Bach Films was to see and hear how Shostakovich's music was used in context. Disembodied scores can be musically effective --  but (for scores I like) I really feel the need to find out how the musically is actually used. The fact that the films were visually pleasing and generally interesting and entertaining was a nice bonus. While the Maxim films are not as remarkable as Kozintsev's and Trauberg's masterpieces, New Babylon and Alone, they are nonetheless of more than simply historical interest.

but (for scores I like) I really feel the need to find out how the musically is actually used. The fact that the films were visually pleasing and generally interesting and entertaining was a nice bonus. While the Maxim films are not as remarkable as Kozintsev's and Trauberg's masterpieces, New Babylon and Alone, they are nonetheless of more than simply historical interest.More screen captures:

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/kozintsev/maxim/vyborg04.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/kozintsev/maxim/vyborg05.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/kozintsev/maxim/vyborg07.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/kozintsev/maxim/vyborg09.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/kozintsev/maxim/vyborg11.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/kozintsev/maxim/vyborg12.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/kozintsev/maxim/vyborg14.png

Comments