Watched December 10-16, 2007 (part two): Mizoguchi and Imai

Gion bayashi / Gion Festival Music / A Geisha (Kenji Mizoguchi, 1953)

The first Mizoguchi films I saw were the two that are most highly touted in the West, Ugetsu and Sansho the Bailiff. While I didn't dislike either of these films -- and I admired Mizoguchi's visual sensibility quite a bit -- neither did I fall in love with with them.

The first Mizoguchi films I saw were the two that are most highly touted in the West, Ugetsu and Sansho the Bailiff. While I didn't dislike either of these films -- and I admired Mizoguchi's visual sensibility quite a bit -- neither did I fall in love with with them.  It was not until I saw Street of Shame that I discovered there was another side to Mizoguchi's work -- one more closely aligned to the world of Ozu and Naruse. When I finally saw Gion Festival Music for the first time, it too was added to the list of Mizoguchi films I liked best.

It was not until I saw Street of Shame that I discovered there was another side to Mizoguchi's work -- one more closely aligned to the world of Ozu and Naruse. When I finally saw Gion Festival Music for the first time, it too was added to the list of Mizoguchi films I liked best.

This film, like Naruse's 1933 Apart From You and 1951 Ginza Cosmetics and Mizoguchi's own 1936 Sisters of Gion, depicts the rather precarious lives of contemporary geisha. All four films involve a pair of women, an older, more experienced one and a younger, comparatively naive one. As in Naruse's two films (and unlike the case in his own older film), the pair of women at the center of attention are presented strictly as distinctive individuals and not primarily as representatives of old and new types of women.

depicts the rather precarious lives of contemporary geisha. All four films involve a pair of women, an older, more experienced one and a younger, comparatively naive one. As in Naruse's two films (and unlike the case in his own older film), the pair of women at the center of attention are presented strictly as distinctive individuals and not primarily as representatives of old and new types of women.

The central figures in Gion bayashi are Miyoharu (Michiyo Kogure), a fastidious, successful 30-something geisha, and Eiko (Ayako Wakao), the teen-aged daughter of a recently-deceased colleague, who had retired to marry a (then) prosperous merchant (Eitaro Shindo).

The central figures in Gion bayashi are Miyoharu (Michiyo Kogure), a fastidious, successful 30-something geisha, and Eiko (Ayako Wakao), the teen-aged daughter of a recently-deceased colleague, who had retired to marry a (then) prosperous merchant (Eitaro Shindo).  Eiko comes to Kyoto to beg Miyoharu to help her become a geisha, having run away from the relatives who have been looking after her following the death of her mother (her father being too preoccupied with his faltering business to take care of a teen-aged girl).

Eiko comes to Kyoto to beg Miyoharu to help her become a geisha, having run away from the relatives who have been looking after her following the death of her mother (her father being too preoccupied with his faltering business to take care of a teen-aged girl).  Training and equipping an apprentice geisha is expensive, and Miyoharu has to borrow lots of money to take care of this. Problems arise when Eiko has finally been fully trained, and the businessman who actually provided the loan, made through Miyoharu's employer Okimi (Chieko Naniwa), wants his extra-monetary payback.

Training and equipping an apprentice geisha is expensive, and Miyoharu has to borrow lots of money to take care of this. Problems arise when Eiko has finally been fully trained, and the businessman who actually provided the loan, made through Miyoharu's employer Okimi (Chieko Naniwa), wants his extra-monetary payback.

Eiko's self-defense tactics leave the client (and financial patron) injured and Okimi furious. This results in a boycott, which will be end only if Miyoharu proves to be suitably "obliging" to a patron who has developed a fancy for her. Desperate, Miyoharu eventually gives in, only to be chided by Eiko for her action.

Eiko's self-defense tactics leave the client (and financial patron) injured and Okimi furious. This results in a boycott, which will be end only if Miyoharu proves to be suitably "obliging" to a patron who has developed a fancy for her. Desperate, Miyoharu eventually gives in, only to be chided by Eiko for her action.  After plenty of recriminations and tears, the two are reconciled -- and Miyoharu promises she will act (in effect) as Eiko's sponsor, and will buffer her from the seamier aspects of the business side of geisha-hood.

After plenty of recriminations and tears, the two are reconciled -- and Miyoharu promises she will act (in effect) as Eiko's sponsor, and will buffer her from the seamier aspects of the business side of geisha-hood.

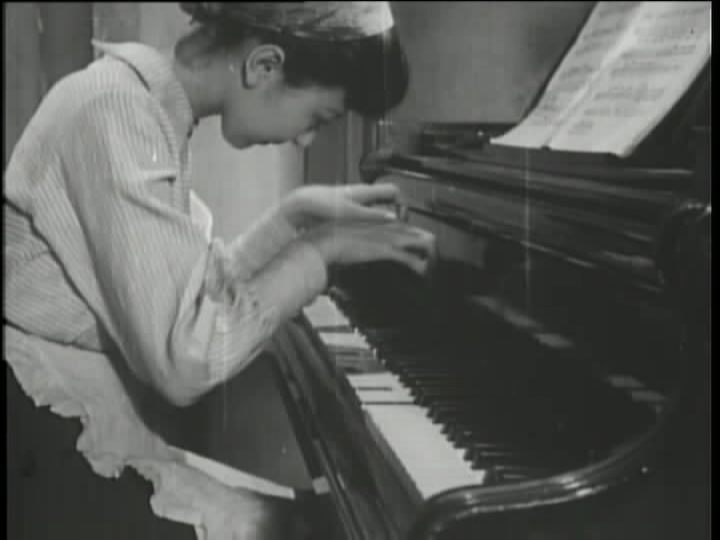

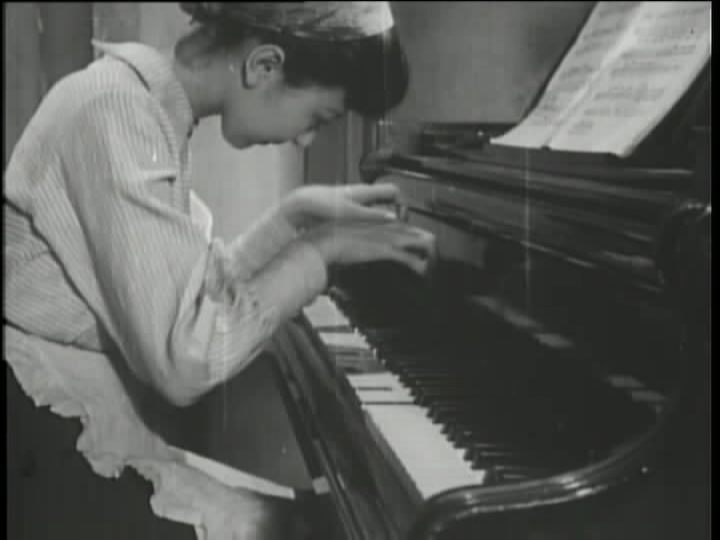

The acting in this film (particularly that of Kogure and 19 year-old Wakao) is excellent -- and the cinematography by Kazuo Miyagawa is absolutely gorgeous. The film is a somewhat curious blend of realism (especially the scenes showing the training of Eiko) and rather lurid sensationalism. It also considerably compressed the time period involved in Eiko's transformation from rank beginner to fully qualified practitioner.

The acting in this film (particularly that of Kogure and 19 year-old Wakao) is excellent -- and the cinematography by Kazuo Miyagawa is absolutely gorgeous. The film is a somewhat curious blend of realism (especially the scenes showing the training of Eiko) and rather lurid sensationalism. It also considerably compressed the time period involved in Eiko's transformation from rank beginner to fully qualified practitioner.  For all Mizoguchi's vaunted familiarity with the world of the geisha, his presentation seems a lot less "real" than Naruse's treatment of the same sort of material in films like Flowing (as well as the other two Naruse films mentioned above). All the same, I wouldn't want to be without a film as lovely and interesting as Gion bayashi -- and it is nice to finally have a good-looking English-subtitled DVD thanks to Masters of Cinema (UK).

For all Mizoguchi's vaunted familiarity with the world of the geisha, his presentation seems a lot less "real" than Naruse's treatment of the same sort of material in films like Flowing (as well as the other two Naruse films mentioned above). All the same, I wouldn't want to be without a film as lovely and interesting as Gion bayashi -- and it is nice to finally have a good-looking English-subtitled DVD thanks to Masters of Cinema (UK).

More images:

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/mizoguchi/gion/bayashi05.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/mizoguchi/gion/bayashi09.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/mizoguchi/gion/bayashi10.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/mizoguchi/gion/bayashi12.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/mizoguchi/gion/bayashi14.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/mizoguchi/gion/bayashi15.png

Koko ni izumi ari / Here Is a Fountain (Tadashi Imai, 1955)

Tadashi Imai was one of Japan's most popular (and award-winning) directors of the 1950s and 1960s. Yet his work is virtually unknown in the West. Richie and Anderson in their 1959 The Japanese Film, alternated between praising (sometimes very highly) particular films and dismissing him and his work overall.

Tadashi Imai was one of Japan's most popular (and award-winning) directors of the 1950s and 1960s. Yet his work is virtually unknown in the West. Richie and Anderson in their 1959 The Japanese Film, alternated between praising (sometimes very highly) particular films and dismissing him and his work overall.  At the root of their dissatisfaction seems to have been the fact that Imai was an unapologetic leftist -- and made no attempt to hide this fact in his films. Time and again, Richie and Anderson return to Imai's politics, claiming too many of his films were nothing but Communist propaganda --

At the root of their dissatisfaction seems to have been the fact that Imai was an unapologetic leftist -- and made no attempt to hide this fact in his films. Time and again, Richie and Anderson return to Imai's politics, claiming too many of his films were nothing but Communist propaganda --  and then deriding him because he got so interested in the details of his films that they turned out to be unconvincing propaganda. One might gently suggest in response that, perhaps, Imai was never so wrapped up in mere propagandizing as Richie and Anderson thought he was.

and then deriding him because he got so interested in the details of his films that they turned out to be unconvincing propaganda. One might gently suggest in response that, perhaps, Imai was never so wrapped up in mere propagandizing as Richie and Anderson thought he was.

In any event, where these early writers had mixed feelings about Imai, Audie Bock in her 1978 Japanese Film Directors expressed nothing but dismissive contempt. Richie, in his A Hundred Years of Japanese Film (2001), is more generally appreciative of Imai's work than he had been decades ago.

In any event, where these early writers had mixed feelings about Imai, Audie Bock in her 1978 Japanese Film Directors expressed nothing but dismissive contempt. Richie, in his A Hundred Years of Japanese Film (2001), is more generally appreciative of Imai's work than he had been decades ago.  Nevertheless, he attributes Imai's effectiveness and individuality more to his movies' themes than to any identifiable cinematic style. Despite this recent critical "rehabilitation", the many decades of critical dismissal have made Imai's work essentially invisible in the West (and particularly in the United States).

Nevertheless, he attributes Imai's effectiveness and individuality more to his movies' themes than to any identifiable cinematic style. Despite this recent critical "rehabilitation", the many decades of critical dismissal have made Imai's work essentially invisible in the West (and particularly in the United States).

The present film is not one of Imai's most brilliant and inspired works. And it does indeed have a somewhat didactic core -- emphasizing the importance of disseminating high culture (here western classical music) to ordinary people outside the big cities. But is is far from the simple-minded affair described by Anderson and Richie:

The present film is not one of Imai's most brilliant and inspired works. And it does indeed have a somewhat didactic core -- emphasizing the importance of disseminating high culture (here western classical music) to ordinary people outside the big cities. But is is far from the simple-minded affair described by Anderson and Richie:

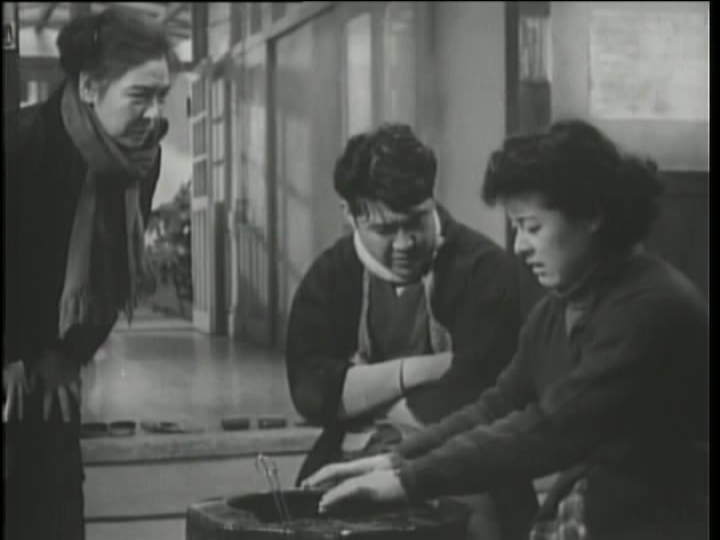

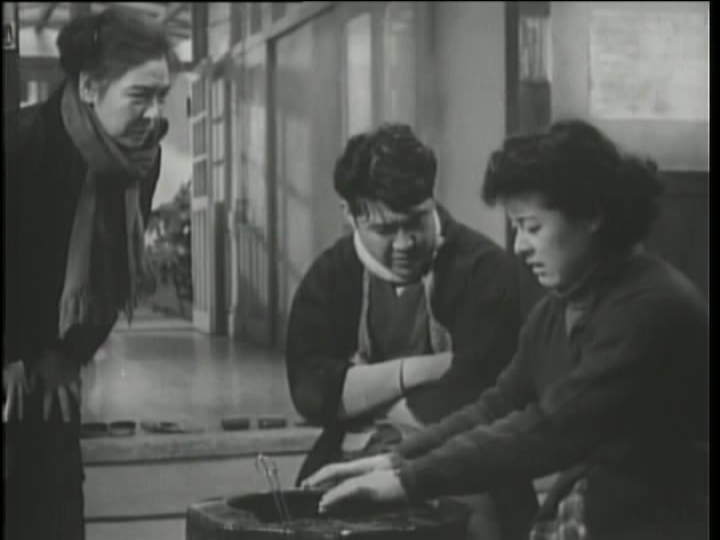

In fact, the film suggests nothing of the sort. The film recounts the (sometimes) rather quixotic efforts of an idealistic group of classical musicians to bring music to people in the boondocks. The musicians are not saints, but ordinary (and very fallible) mortals -- and they live a hand to mouth existence most of the time.

In fact, the film suggests nothing of the sort. The film recounts the (sometimes) rather quixotic efforts of an idealistic group of classical musicians to bring music to people in the boondocks. The musicians are not saints, but ordinary (and very fallible) mortals -- and they live a hand to mouth existence most of the time.  Their efforts do not always meet with success -- some school audiences (and their parents) are frankly bored to tears. In other places, they can scarcely find opportunities to play. To be sure, the group does get particularly good reception in one remote rural school --

Their efforts do not always meet with success -- some school audiences (and their parents) are frankly bored to tears. In other places, they can scarcely find opportunities to play. To be sure, the group does get particularly good reception in one remote rural school --  but this would seem to be not just any old school but the famed Yamabiko Gakko, previously portrayed in Imai's 1952 film of that name. They also get an enthusiastic receptions by a group of farmers and the patients at a hospital for lepers -- but surely the novelty of the experience and gratitude towards people who would make such great effort to bring music to them explains some of the attentiveness of these naive audiences.

but this would seem to be not just any old school but the famed Yamabiko Gakko, previously portrayed in Imai's 1952 film of that name. They also get an enthusiastic receptions by a group of farmers and the patients at a hospital for lepers -- but surely the novelty of the experience and gratitude towards people who would make such great effort to bring music to them explains some of the attentiveness of these naive audiences.  And the finale of the film involves a performance in Tokyo of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony (with some of the group's members playing in the orchestra and others in the audience) -- and the upscale urban audience at this concert shows no lack of interest or receptivity.

And the finale of the film involves a performance in Tokyo of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony (with some of the group's members playing in the orchestra and others in the audience) -- and the upscale urban audience at this concert shows no lack of interest or receptivity.

Any political point the film might be making seems to me secondary to Imai's interest in depicting the story of his unusual group of musicians. And to help ensure audience interest in his characters, Imai was not averse to using very familiar faces in his cast,

Any political point the film might be making seems to me secondary to Imai's interest in depicting the story of his unusual group of musicians. And to help ensure audience interest in his characters, Imai was not averse to using very familiar faces in his cast,  which included Keiko Kishi, Eiji Okada, Keiju Kobayashi, Koji Mitsui, Daisuke Katô, Sadako Sawamura, Eijirô Tono, Hisako Hara and Noriko Sengoku. Despite the recognizability of the principal cast members, Imai manages to create an almost documentary-esque feel for his film (integrating non-professionals with his veteran performers).

which included Keiko Kishi, Eiji Okada, Keiju Kobayashi, Koji Mitsui, Daisuke Katô, Sadako Sawamura, Eijirô Tono, Hisako Hara and Noriko Sengoku. Despite the recognizability of the principal cast members, Imai manages to create an almost documentary-esque feel for his film (integrating non-professionals with his veteran performers).

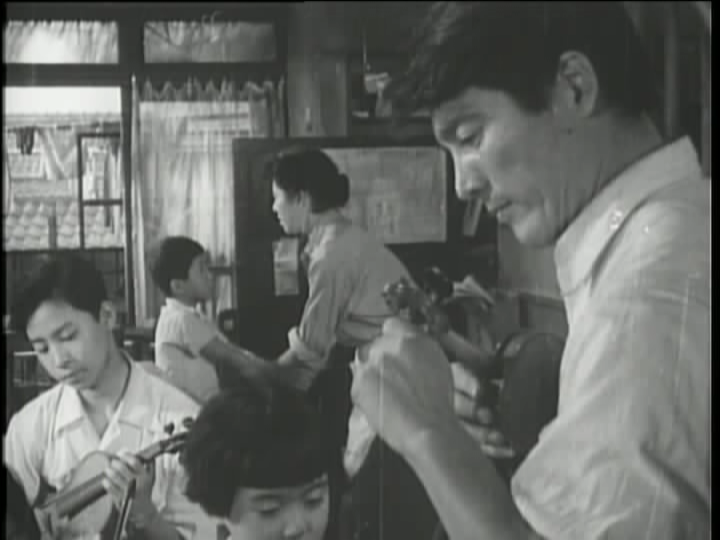

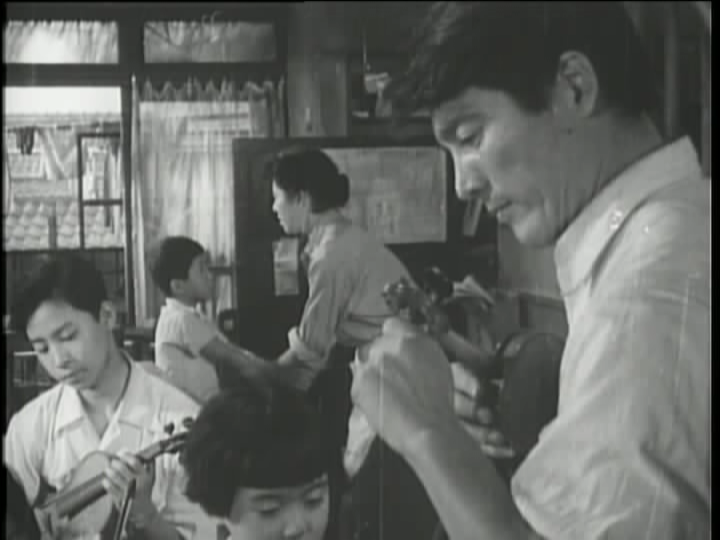

There is very little point in summarizing the plot here, but one can note that the core character is a violinist played by Eiji Okada. The other most important characters are Keiko Kishi, a pianist (and eventually Okada's wife) and Keiju Kobayashi, more or less the music director of the group, who lets his obsession with music wreck his domestic life. The cast is uniformly effective -- and there is undeniable meta-cinematic fun in watching Daisuke Kato banging drums and Koji Mitsui playing trumpet and the like.

There is very little point in summarizing the plot here, but one can note that the core character is a violinist played by Eiji Okada. The other most important characters are Keiko Kishi, a pianist (and eventually Okada's wife) and Keiju Kobayashi, more or less the music director of the group, who lets his obsession with music wreck his domestic life. The cast is uniformly effective -- and there is undeniable meta-cinematic fun in watching Daisuke Kato banging drums and Koji Mitsui playing trumpet and the like.  The script is by Yôko Mizuki (who crafted many fine scripts for Imai and Naruse, among others) and the cinematography by Shunichiro Nakao (who shot not only many of Imai's best films but also Naruse's remarkable but neglected Haru no mezame). The film is available on DVD in Japan, but not with English subtitles (of course).

The script is by Yôko Mizuki (who crafted many fine scripts for Imai and Naruse, among others) and the cinematography by Shunichiro Nakao (who shot not only many of Imai's best films but also Naruse's remarkable but neglected Haru no mezame). The film is available on DVD in Japan, but not with English subtitles (of course).

The first Mizoguchi films I saw were the two that are most highly touted in the West, Ugetsu and Sansho the Bailiff. While I didn't dislike either of these films -- and I admired Mizoguchi's visual sensibility quite a bit -- neither did I fall in love with with them.

The first Mizoguchi films I saw were the two that are most highly touted in the West, Ugetsu and Sansho the Bailiff. While I didn't dislike either of these films -- and I admired Mizoguchi's visual sensibility quite a bit -- neither did I fall in love with with them.  It was not until I saw Street of Shame that I discovered there was another side to Mizoguchi's work -- one more closely aligned to the world of Ozu and Naruse. When I finally saw Gion Festival Music for the first time, it too was added to the list of Mizoguchi films I liked best.

It was not until I saw Street of Shame that I discovered there was another side to Mizoguchi's work -- one more closely aligned to the world of Ozu and Naruse. When I finally saw Gion Festival Music for the first time, it too was added to the list of Mizoguchi films I liked best.This film, like Naruse's 1933 Apart From You and 1951 Ginza Cosmetics and Mizoguchi's own 1936 Sisters of Gion,

depicts the rather precarious lives of contemporary geisha. All four films involve a pair of women, an older, more experienced one and a younger, comparatively naive one. As in Naruse's two films (and unlike the case in his own older film), the pair of women at the center of attention are presented strictly as distinctive individuals and not primarily as representatives of old and new types of women.

depicts the rather precarious lives of contemporary geisha. All four films involve a pair of women, an older, more experienced one and a younger, comparatively naive one. As in Naruse's two films (and unlike the case in his own older film), the pair of women at the center of attention are presented strictly as distinctive individuals and not primarily as representatives of old and new types of women. The central figures in Gion bayashi are Miyoharu (Michiyo Kogure), a fastidious, successful 30-something geisha, and Eiko (Ayako Wakao), the teen-aged daughter of a recently-deceased colleague, who had retired to marry a (then) prosperous merchant (Eitaro Shindo).

The central figures in Gion bayashi are Miyoharu (Michiyo Kogure), a fastidious, successful 30-something geisha, and Eiko (Ayako Wakao), the teen-aged daughter of a recently-deceased colleague, who had retired to marry a (then) prosperous merchant (Eitaro Shindo).  Eiko comes to Kyoto to beg Miyoharu to help her become a geisha, having run away from the relatives who have been looking after her following the death of her mother (her father being too preoccupied with his faltering business to take care of a teen-aged girl).

Eiko comes to Kyoto to beg Miyoharu to help her become a geisha, having run away from the relatives who have been looking after her following the death of her mother (her father being too preoccupied with his faltering business to take care of a teen-aged girl).  Training and equipping an apprentice geisha is expensive, and Miyoharu has to borrow lots of money to take care of this. Problems arise when Eiko has finally been fully trained, and the businessman who actually provided the loan, made through Miyoharu's employer Okimi (Chieko Naniwa), wants his extra-monetary payback.

Training and equipping an apprentice geisha is expensive, and Miyoharu has to borrow lots of money to take care of this. Problems arise when Eiko has finally been fully trained, and the businessman who actually provided the loan, made through Miyoharu's employer Okimi (Chieko Naniwa), wants his extra-monetary payback. Eiko's self-defense tactics leave the client (and financial patron) injured and Okimi furious. This results in a boycott, which will be end only if Miyoharu proves to be suitably "obliging" to a patron who has developed a fancy for her. Desperate, Miyoharu eventually gives in, only to be chided by Eiko for her action.

Eiko's self-defense tactics leave the client (and financial patron) injured and Okimi furious. This results in a boycott, which will be end only if Miyoharu proves to be suitably "obliging" to a patron who has developed a fancy for her. Desperate, Miyoharu eventually gives in, only to be chided by Eiko for her action.  After plenty of recriminations and tears, the two are reconciled -- and Miyoharu promises she will act (in effect) as Eiko's sponsor, and will buffer her from the seamier aspects of the business side of geisha-hood.

After plenty of recriminations and tears, the two are reconciled -- and Miyoharu promises she will act (in effect) as Eiko's sponsor, and will buffer her from the seamier aspects of the business side of geisha-hood. The acting in this film (particularly that of Kogure and 19 year-old Wakao) is excellent -- and the cinematography by Kazuo Miyagawa is absolutely gorgeous. The film is a somewhat curious blend of realism (especially the scenes showing the training of Eiko) and rather lurid sensationalism. It also considerably compressed the time period involved in Eiko's transformation from rank beginner to fully qualified practitioner.

The acting in this film (particularly that of Kogure and 19 year-old Wakao) is excellent -- and the cinematography by Kazuo Miyagawa is absolutely gorgeous. The film is a somewhat curious blend of realism (especially the scenes showing the training of Eiko) and rather lurid sensationalism. It also considerably compressed the time period involved in Eiko's transformation from rank beginner to fully qualified practitioner.  For all Mizoguchi's vaunted familiarity with the world of the geisha, his presentation seems a lot less "real" than Naruse's treatment of the same sort of material in films like Flowing (as well as the other two Naruse films mentioned above). All the same, I wouldn't want to be without a film as lovely and interesting as Gion bayashi -- and it is nice to finally have a good-looking English-subtitled DVD thanks to Masters of Cinema (UK).

For all Mizoguchi's vaunted familiarity with the world of the geisha, his presentation seems a lot less "real" than Naruse's treatment of the same sort of material in films like Flowing (as well as the other two Naruse films mentioned above). All the same, I wouldn't want to be without a film as lovely and interesting as Gion bayashi -- and it is nice to finally have a good-looking English-subtitled DVD thanks to Masters of Cinema (UK).More images:

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/mizoguchi/gion/bayashi05.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/mizoguchi/gion/bayashi09.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/mizoguchi/gion/bayashi10.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/mizoguchi/gion/bayashi12.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/mizoguchi/gion/bayashi14.png

http://i9.photobucket.com/albums/a59/mkerpan/mizoguchi/gion/bayashi15.png

Koko ni izumi ari / Here Is a Fountain (Tadashi Imai, 1955)

Tadashi Imai was one of Japan's most popular (and award-winning) directors of the 1950s and 1960s. Yet his work is virtually unknown in the West. Richie and Anderson in their 1959 The Japanese Film, alternated between praising (sometimes very highly) particular films and dismissing him and his work overall.

Tadashi Imai was one of Japan's most popular (and award-winning) directors of the 1950s and 1960s. Yet his work is virtually unknown in the West. Richie and Anderson in their 1959 The Japanese Film, alternated between praising (sometimes very highly) particular films and dismissing him and his work overall.  At the root of their dissatisfaction seems to have been the fact that Imai was an unapologetic leftist -- and made no attempt to hide this fact in his films. Time and again, Richie and Anderson return to Imai's politics, claiming too many of his films were nothing but Communist propaganda --

At the root of their dissatisfaction seems to have been the fact that Imai was an unapologetic leftist -- and made no attempt to hide this fact in his films. Time and again, Richie and Anderson return to Imai's politics, claiming too many of his films were nothing but Communist propaganda --  and then deriding him because he got so interested in the details of his films that they turned out to be unconvincing propaganda. One might gently suggest in response that, perhaps, Imai was never so wrapped up in mere propagandizing as Richie and Anderson thought he was.

and then deriding him because he got so interested in the details of his films that they turned out to be unconvincing propaganda. One might gently suggest in response that, perhaps, Imai was never so wrapped up in mere propagandizing as Richie and Anderson thought he was. In any event, where these early writers had mixed feelings about Imai, Audie Bock in her 1978 Japanese Film Directors expressed nothing but dismissive contempt. Richie, in his A Hundred Years of Japanese Film (2001), is more generally appreciative of Imai's work than he had been decades ago.

In any event, where these early writers had mixed feelings about Imai, Audie Bock in her 1978 Japanese Film Directors expressed nothing but dismissive contempt. Richie, in his A Hundred Years of Japanese Film (2001), is more generally appreciative of Imai's work than he had been decades ago.  Nevertheless, he attributes Imai's effectiveness and individuality more to his movies' themes than to any identifiable cinematic style. Despite this recent critical "rehabilitation", the many decades of critical dismissal have made Imai's work essentially invisible in the West (and particularly in the United States).

Nevertheless, he attributes Imai's effectiveness and individuality more to his movies' themes than to any identifiable cinematic style. Despite this recent critical "rehabilitation", the many decades of critical dismissal have made Imai's work essentially invisible in the West (and particularly in the United States). The present film is not one of Imai's most brilliant and inspired works. And it does indeed have a somewhat didactic core -- emphasizing the importance of disseminating high culture (here western classical music) to ordinary people outside the big cities. But is is far from the simple-minded affair described by Anderson and Richie:

The present film is not one of Imai's most brilliant and inspired works. And it does indeed have a somewhat didactic core -- emphasizing the importance of disseminating high culture (here western classical music) to ordinary people outside the big cities. But is is far from the simple-minded affair described by Anderson and Richie:Especially interesting was the films suggestion that only in the Japanese peasant and laboring class is there any real appreciation for the inner substance of the music.

In fact, the film suggests nothing of the sort. The film recounts the (sometimes) rather quixotic efforts of an idealistic group of classical musicians to bring music to people in the boondocks. The musicians are not saints, but ordinary (and very fallible) mortals -- and they live a hand to mouth existence most of the time.

In fact, the film suggests nothing of the sort. The film recounts the (sometimes) rather quixotic efforts of an idealistic group of classical musicians to bring music to people in the boondocks. The musicians are not saints, but ordinary (and very fallible) mortals -- and they live a hand to mouth existence most of the time.  Their efforts do not always meet with success -- some school audiences (and their parents) are frankly bored to tears. In other places, they can scarcely find opportunities to play. To be sure, the group does get particularly good reception in one remote rural school --

Their efforts do not always meet with success -- some school audiences (and their parents) are frankly bored to tears. In other places, they can scarcely find opportunities to play. To be sure, the group does get particularly good reception in one remote rural school --  but this would seem to be not just any old school but the famed Yamabiko Gakko, previously portrayed in Imai's 1952 film of that name. They also get an enthusiastic receptions by a group of farmers and the patients at a hospital for lepers -- but surely the novelty of the experience and gratitude towards people who would make such great effort to bring music to them explains some of the attentiveness of these naive audiences.

but this would seem to be not just any old school but the famed Yamabiko Gakko, previously portrayed in Imai's 1952 film of that name. They also get an enthusiastic receptions by a group of farmers and the patients at a hospital for lepers -- but surely the novelty of the experience and gratitude towards people who would make such great effort to bring music to them explains some of the attentiveness of these naive audiences.  And the finale of the film involves a performance in Tokyo of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony (with some of the group's members playing in the orchestra and others in the audience) -- and the upscale urban audience at this concert shows no lack of interest or receptivity.

And the finale of the film involves a performance in Tokyo of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony (with some of the group's members playing in the orchestra and others in the audience) -- and the upscale urban audience at this concert shows no lack of interest or receptivity. Any political point the film might be making seems to me secondary to Imai's interest in depicting the story of his unusual group of musicians. And to help ensure audience interest in his characters, Imai was not averse to using very familiar faces in his cast,

Any political point the film might be making seems to me secondary to Imai's interest in depicting the story of his unusual group of musicians. And to help ensure audience interest in his characters, Imai was not averse to using very familiar faces in his cast,  which included Keiko Kishi, Eiji Okada, Keiju Kobayashi, Koji Mitsui, Daisuke Katô, Sadako Sawamura, Eijirô Tono, Hisako Hara and Noriko Sengoku. Despite the recognizability of the principal cast members, Imai manages to create an almost documentary-esque feel for his film (integrating non-professionals with his veteran performers).

which included Keiko Kishi, Eiji Okada, Keiju Kobayashi, Koji Mitsui, Daisuke Katô, Sadako Sawamura, Eijirô Tono, Hisako Hara and Noriko Sengoku. Despite the recognizability of the principal cast members, Imai manages to create an almost documentary-esque feel for his film (integrating non-professionals with his veteran performers). There is very little point in summarizing the plot here, but one can note that the core character is a violinist played by Eiji Okada. The other most important characters are Keiko Kishi, a pianist (and eventually Okada's wife) and Keiju Kobayashi, more or less the music director of the group, who lets his obsession with music wreck his domestic life. The cast is uniformly effective -- and there is undeniable meta-cinematic fun in watching Daisuke Kato banging drums and Koji Mitsui playing trumpet and the like.

There is very little point in summarizing the plot here, but one can note that the core character is a violinist played by Eiji Okada. The other most important characters are Keiko Kishi, a pianist (and eventually Okada's wife) and Keiju Kobayashi, more or less the music director of the group, who lets his obsession with music wreck his domestic life. The cast is uniformly effective -- and there is undeniable meta-cinematic fun in watching Daisuke Kato banging drums and Koji Mitsui playing trumpet and the like.  The script is by Yôko Mizuki (who crafted many fine scripts for Imai and Naruse, among others) and the cinematography by Shunichiro Nakao (who shot not only many of Imai's best films but also Naruse's remarkable but neglected Haru no mezame). The film is available on DVD in Japan, but not with English subtitles (of course).

The script is by Yôko Mizuki (who crafted many fine scripts for Imai and Naruse, among others) and the cinematography by Shunichiro Nakao (who shot not only many of Imai's best films but also Naruse's remarkable but neglected Haru no mezame). The film is available on DVD in Japan, but not with English subtitles (of course).

Comments